My Dress-Up Darling/Kisekoi è sempre stato affascinante, ma ha raggiunto un nuovo livello con un seguito che è più selvaggiamente creativo, tematicamente più serrato e, in questo processo, più diversificato nelle sottoculture che esplora. Analizziamo i cambiamenti di produzione che hanno dato ottimi risultati!

La prima stagione di My Dress Up Darling/Sono Bisque Doll wa Koi wo Suru, che chiameremo Kisekoi per risparmiarci quel boccone di titolo, è stato un adattamento perfettamente ragionevole di una serie divertente. Si trattava, tuttavia, di un incapsulamento un po’ riduttivo di ciò che racchiude l’opera originale. Intendiamoci, questo non è sempre un aspetto negativo, per non parlare di un rompicapo. Semmai, potresti sostenere che è naturale che gli adattamenti si presentino in questo modo; è molto più semplice progettare un’esperienza strettamente focalizzata con la lungimiranza di pubblicazioni in corso o addirittura finite, mentre gli autori originali che hanno appena iniziato il loro lavoro lottano con l’ignoto. Alcune serie sono state chiaramente migliorate attraverso i loro adattamenti a causa di ciò, sia eliminando elementi che in retrospettiva risultavano scomodi, sia attraverso semplici scelte di enfasi.

Quando si tratta di Kisekoi, però, non credo che sia stato il caso. Ancora una volta, non prenderla come una dura critica al suo primo programma televisivo, che nel complesso era solido. Chiunque lo abbia visto può attestare che la sua resa variava da tecnicamente valida a talvolta eccezionale, con standard di animazione ben al di sopra della norma degli attuali anime televisivi. Eppure, l’arrivo del suo seguito dimostra l’esistenza di un potenziale più ampio che non sono riusciti a sfruttare la prima volta.

La relativa ristrettezza della stagione 1 è iniziata con un aspetto di cui difficilmente si può criticare il team creativo per: il conteggio degli episodi. Con un unico corso a disposizione, lo staff ha fatto la scelta migliore a sua disposizione e ha proceduto con un ritmo misurato, anche se ciò significava non raggiungere gli archi (i più recenti per l’epoca) in cui il manga ha davvero fatto il suo passo. Anche se sempre divertente, il lavoro di Shinichi Fukuda impiega un po’di tempo per elevarsi da una commedia romantica carina che afferma un messaggio che suona carino, a una in cui quelle convinzioni risuonano in ogni pagina con quel tipo di convinzione a cui non puoi fare a meno di credere.

In termini più specifici, ciò significa che la serie amplia gradualmente i suoi orizzonti nella rappresentazione della cultura cosplay e otaku nel suo complesso. Il suo rispetto per il primo non può mai essere messo in discussione; più di alcuni capitoli della serie, comprese le fasi precedenti, sono così approfonditi nella rappresentazione dell’hobby che potrebbero servire come tutorial. Ciò si è tradotto anche nella prima stagione dell’anime, offrendo uno sguardo indiscutibilmente amorevole alla sottocultura… o meglio, alla fetta di essa presente nel materiale che avrebbero avuto il tempo di adattare. Ciò è bastato per indicare idee come il fandom proattivo e la creazione derivata come modi preziosi per incanalare il tuo amore, così come per respingere la pressione sociale su ciò che dovremmo apprezzare. Sebbene questi siano temi che accompagnano naturalmente Gojo e Marin durante la loro storia d’amore in erba, in questa fase non sono ancora completamente formati. I concetti sembrano in qualche modo distaccati dai punti salienti della produzione e semplicemente non sono affatto collegati alle realtà della maggior parte delle persone all’interno della cultura che esplora. Questi temi sono, in breve, un’adeguata vetrina per una bella commedia romantica.

In una certa misura, quella ristrettezza di sapore si riduce all’esecuzione. Se ti dico di chiudere gli occhi e immaginare alcune sequenze memorabili della prima stagione, so per certo che ti è venuta in mente una combinazione di rappresentazione vivace e volumetrica del corpo di Marin in abiti succinti. Questo non è un tentativo di svergognare i pervertiti tra i nostri lettori: nei siti mirati all’apprezzamento dell’arte, la perversione è in primo luogo una sorta di distintivo d’onore. Ciò che intendo dire, però, è che quelle sequenze hanno ricevuto un livello di consegna memorabile e chiaramente eccezionale che la serie non poteva permettersi regolarmente. È una disuguaglianza nel valore dell’impatto (anche se il pavimento è ancora rispettabile) che dà la falsa impressione che quei momenti siano tutto ciò di cui parla la serie.

Vale la pena notare che, quando si guarda indietro alla prima stagione per una serie di interviste di Febri, direttore della serieDirettore della serie: (監督, kantoku): la persona responsabile dell’intera produzione, sia come decisore creativo che come supervisore finale. Superano il resto dello staff e alla fine hanno l’ultima parola. Esistono tuttavia serie con diversi livelli di registi: regista capo, assistente alla regia, regista di episodi della serie, tutti i tipi di ruoli non standard. La gerarchia in questi casi varia caso per caso. Keisuke Shinohara ha ammesso di aver inizialmente pensato che Kisekoi fosse semplicemente un piacere per gli occhi dei ragazzi. Fu solo dopo aver letto oltre che si trovò profondamente attratto dalle lotte di Gojo come creatore; pur operando in campi diversi, ha trovato il suo arco narrativo in sintonia con chiunque fosse interessato a creare cose. È stato anche approfondendo maggiormente la serie che è arrivato ad apprezzare la rappresentazione dei sentimenti di Marin in un modo definito e altrettanto importante, in contrasto con la tendenza delle commedie romantiche danseimuke di inquadrare le donne come oggetti inconoscibili di ricerca. Questo sembra essere un sentimento condiviso da tutto il team, dato che il produttore capo di Aniplex Nobuhiro Nakayama ha recentemente fatto riferimento all’energia shoujo della serie per questo motivo.

Detto questo, ci sono più aspetti nella serie non significa che l’erotismo non sia sempre stato parte di Kisekoi. Seguiamo due adolescenti, ciascuno dal proprio punto di imbarazzo, cercando di capire la propria sessualità. Una di loro è abbastanza sicura del proprio corpo da tentare di fare cosplay per personaggi provocanti di giochi per adulti; sottolineando il rapporto tra una serie con questo tema e la rappresentazione dei corpi, oltre al fatto che le piacciono molto i giochi porno. E, cosa probabilmente più importante, Fukuda non nasconde che le piace rappresentare Marin in modo sexy. Considerata questa premessa e l’accesso da parte del team ad alcuni eccezionali disegnatori di personaggi che daranno volentieri il massimo in quelle sequenze, non è né una sorpresa né uno svantaggio che molti momenti salienti della prima stagione corrispondano ai tagli audaci di Marin. Se giudichiamo puramente l’esecuzione, il problema riguarda più, sia per percezione che per debolezza relativa, gli altri lati di Kisekoi S1 che non hanno colpito con la stessa forza.

Per cominciare, è importante ricordare il contesto della produzione di quella prima stagione. Sebbene sia ben realizzato per gli standard degli anime televisivi, non possiamo dimenticare che seguì l’implosione assoluta di Wonder Egg Priority. Sebbene l’ambizione di Shouta Umehara come produttore di animazione alimenti quello che è senza dubbio il team più prestigioso di CloverWorks, a volte ha esagerato al punto da diventare anche lui problematico. Non è affatto un leader crudele che sfrutta gli altri, ma piuttosto un tipo avventato che guida anche le missioni suicide; non dimenticare che la persona WEP inviata in ospedale era lui stesso. Il suo atteggiamento in quel momento è qualcosa che si è gradualmente evoluto – in modi che avrebbero poi influenzato la seconda stagione di Kisekoi – ma più di ogni altra cosa, è stata quell’esaurimento mentale e fisico post-WEP che ha trascinato con i piedi per terra gli standard per il loro prossimo progetto. La prima stagione di Kisekoi ha accettato una soglia più bassa di coerenza e qualità per la grafica dei personaggi e, notoriamente, prevedeva due episodi completamente esternalizzati (#03 per Traumerei Animation Studio e #07 per Lapin Track). È una produzione solida, ma anche la definizione stessa di trattenersi. Considerato questo contesto, è comprensibile.

Un altro motivo per cui l’inquadratura occasionale di Marin risaltava su quasi tutto il resto, e il motivo per cui abbiamo introdotto in precedenza l’idea di percezione, è quel regista della serieRegista della serie: (監督, kantoku): la persona responsabile dell’intera produzione, sia come decisore creativo che come supervisore finale. Superano il resto dello staff e alla fine hanno l’ultima parola. Esistono tuttavia serie con diversi livelli di registi: regista capo, assistente alla regia, regista di episodi della serie, tutti i tipi di ruoli non standard. La gerarchia in questi casi varia caso per caso. Shinohara è poco appariscente per natura. L’inizio della prima stagione era già sufficiente per dimostrare che, anche quando esagera, lo fa in un modo così calcolato da dare per scontato il suo modo convincente. Attraverso la tecnica e l’arguzia, usa la sua posizione di regista per proteggere l’immersione dello spettatore da qualsiasi frantumazione. Potrebbe non essere un realista rigoroso, ma ha il tipo di visione radicata che lo costringe a ritrarre i riflettori figurativi nello stesso modo in cui mostreresti le luci vere. Sebbene non abbia mai messo da parte il senso dell’umorismo dell’opera originale, sono stati altri registi di episodi della prima stagione ad appoggiarsi più apparentemente ad esso. Soprattutto allora, Shinohara era felice di puntare a una sensazione di trasparenza; essere autentici nel rappresentare le persone e l’argomento, lasciando l’artificio agli altri.

Quando si arriva a quella prima stagione, episodi come #11 hanno offerto il tipo di attrito a cui Shinohara è più naturalmente avverso; seguendo l’esempio di un certo regista che è stato poi messo in prima linea nel sequel, ha mostrato un Kisekoi più sfacciato che era disposto a giocare con la natura farsesca dei personaggi come risorse 2D con cui giocare. Ma, da una prospettiva completamente diversa, il vero momento clou è stato l’ottavo episodio condotto da Yusuke Kawakami. All’inizio, una lunga chiave di scena animata da Kerorira mostra il tipo di rappresentazione carismatica delle lenzuola che altrimenti vedremo solo nelle scene piccanti durante la prima stagione. Man mano che ci si avventura ulteriormente nell’episodio, la rappresentazione di una vecchia serie di ragazze magiche fa concessioni all’autenticità in favore della regola del cool. Un senso di atmosfera molto più palpabile di quello che si incontra nel resto dello spettacolo, oscilla tra paura e vulnerabilità quando un personaggio si apre a Gojo, per poi passare altrettanto rapidamente a esilaranti dirottamenti visivi.

In contrasto con la discrezione di Shinohara, Lo storyboard di KawakamiStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): i progetti dell’animazione. Una serie di disegni solitamente semplici che servono come sceneggiatura visiva dell’anime, disegnati su fogli speciali con campi per il numero del taglio dell’animazione, note per il rigo e le linee di dialogo corrispondenti. Altro è il tipo che ti ferma con orgoglio sul tuo cammino. C’è un senso di eleganza condiviso che gli consente di esistere all’interno della struttura del regista della serie, ma l’esecuzione è molto più ostentata e palese. Non guardare oltre la svolta di Juju sulla sua identità e sui suoi sogni, trasmessa attraverso una chiara sovrapposizione del suo riflesso e un vestito da ragazza magica. L’intero segmento finale con Marin e Gojo sulla spiaggia è una rappresentazione eterea di primati; del primo amore, delle prime uscite in spiaggia e della prima volta che un gabbiano ti manca di rispetto, perché rimane sciocco anche con quelle vibrazioni ultraterrene che Kawakami e il resto della squadra glielo hanno concesso. L’episodio presenta, da cima a fondo, maestria superlativa e un’interpretazione davvero memorabile all’interno di una stagione in cui i picchi tendono altrimenti ad avere un sapore unico.

Non si può negare che ci sia una differenza fondamentale tra la direzione di un individuo straordinario come Kawakami e la mano ferma di Shinohara. Il regista della serieDirettore della serie: (監督, kantoku): la persona responsabile dell’intera produzione, sia come decisore creativo che come supervisore finale. Superano il resto dello staff e alla fine hanno l’ultima parola. Esistono tuttavia serie con diversi livelli di registi: regista capo, assistente alla regia, regista di episodi della serie, tutti i tipi di ruoli non standard. La gerarchia in questi casi varia caso per caso. lui stesso ne ha fatto allusione, come visto in una delle tante interviste rilasciate per il lungometraggio Kisekoi S2 su Newtype nel settembre 2025. Dato il suo stile premuroso ma alla fine piuttosto tranquillo, Shinohara nega umilmente di avere il tipo di gravità dei suoi colleghi più carismatici. Sebbene in questo settore esista uno schema in cui il magnetismo è correlato alla stravaganza, Shinohara sembra essere palesemente in errore, come si vede dal modo in cui le star più famose cantano il suo nome ogni volta che appare nelle notizie, mostrando apprezzamento per la sua arte in un modo divertente. Forse non risalta allo stesso modo, ma la precisione tecnica di Shinohara è molto apprezzata da chi lavora al suo fianco. E se venisse collocato in un ambiente più favorevole, con anche un po’più di esperienza alle spalle, potrebbe conquistare i telespettatori con altrettanto entusiasmo. La sua grandezza potrebbe essere più difficile da comprendere rispetto a registi più espliciti, ma il suo fascino non è da meno.

E quindi, ecco Kisekoi Stagione 2, il progetto che ha permesso a Shinohara di essere all’altezza di quel potenziale.

Se sei rimasto sorpreso dal modo in cui questo sequel migliora essenzialmente in ogni singola area, avevi la mentalità giusta. Escludendo la rara sostituzione del personale che si risolve in meglio, il risultato più naturale per i sequel è iniziare una leggera tendenza al ribasso. Il mantenimento del livello originale o anche un leggero miglioramento sono nelle carte, ma qualsiasi cosa più promettente di ciò flirta con l’illusione. Per dirla semplicemente, è normale che i progetti iniziali siano sinonimo di investimenti più forti e di team più potenti; dopo tutto, l’impegno a lungo termine di personale qualificato è la cosa più difficile da garantire e, per natura, i sequel arrivano con una base di fan già assicurata o con la certezza che la serie non sarà un successo. Non è che non esistano esempi di seconde stagioni che siano opere più forti e avvincenti, ma di certo non si possono dare per scontati grandi aggiornamenti nel reparto di produzione.

Che cosa ha permesso a Kisekoi di fare un salto così netto, allora? Abbiamo già menzionato alcuni motivi che sono entrati in gioco. Vale la pena ricordare che questo è solo il quarto tentativo di Shinohara come regista di una serie, e che i primi due casi sono stati Black Fox (dove era una sorta di sostituto dell’impegnato Kazuya Nomura) più il guscio crollante di A3 che ha condiviso con un altro regista emergente, Masato Nakazono. Kisekoi sembra il suo primo tentativo di guidare un progetto serio, quindi un miglioramento considerevole al momento del sequel è ragionevole. Soprattutto se, rispetto alla depressione post-WEP, questo progetto è arrivato in un momento in cui la linea di produzione di Umehara e alcune parti di CloverWorks sono… fiorenti il più possibile pur essendo palesemente troppo occupate, diciamo. Non è l’ideale, ma è chiaramente un ambiente migliore per un regista di serie più maturoRegista della serie: (監督, kantoku): la persona responsabile dell’intera produzione, sia come decisore creativo che come supervisore finale. Superano il resto dello staff e alla fine hanno l’ultima parola. Esistono tuttavia serie con diversi livelli di registi: regista capo, assistente alla regia, regista di episodi della serie, tutti i tipi di ruoli non standard. La gerarchia in questi casi è uno scenario caso per caso..

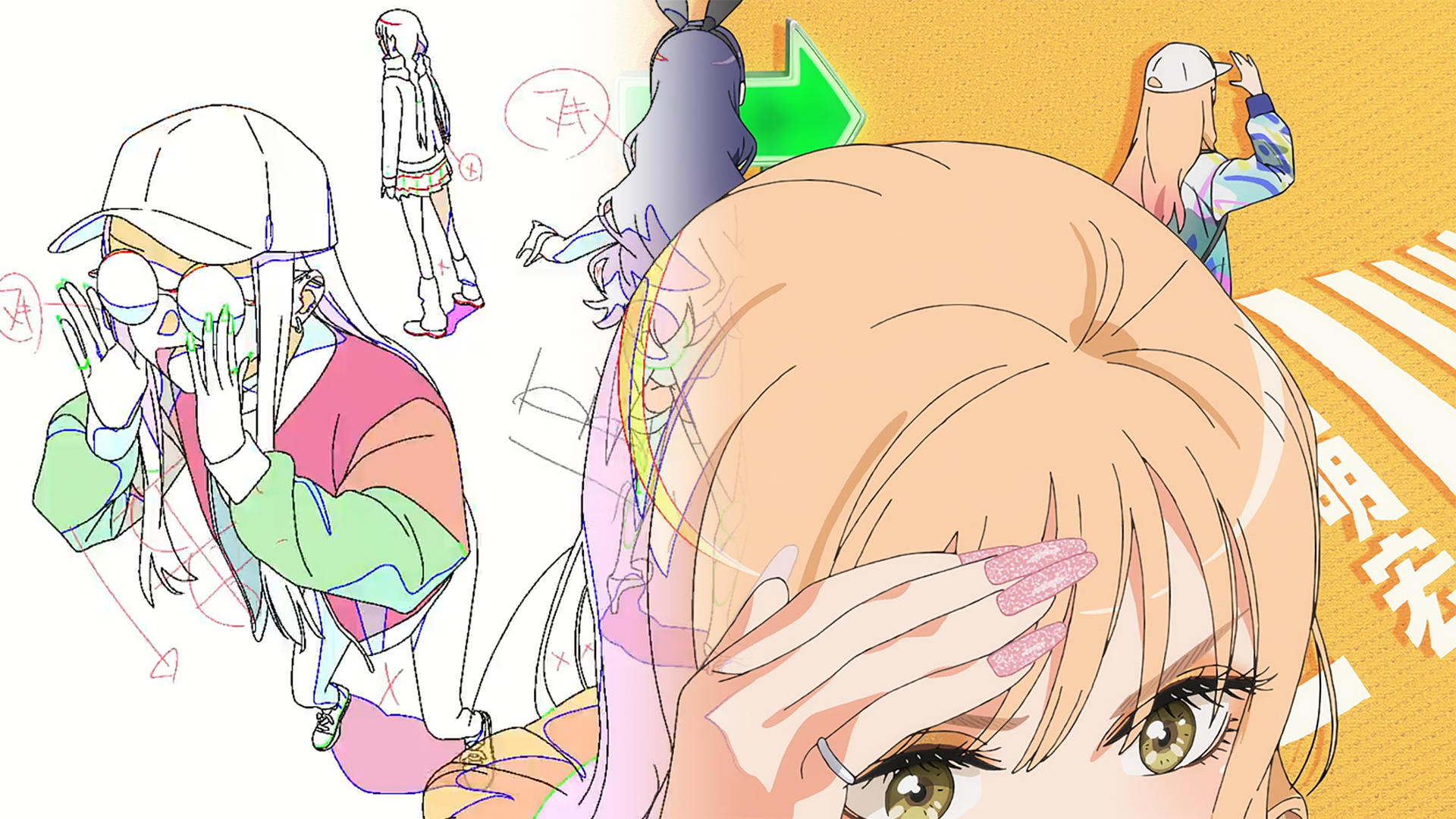

Saltare direttamente al primo episodio della stagione 2, ovvero Kisekoi n. 13 seguendo la numerazione ufficiale, mostra questi miglioramenti sostanziali su tutta la linea. Shinohara non ha mai abbandonato le sue tendenze, ma come ha spiegato nella già citata intervista a Newtype, voleva ampliare la gamma di espressione. A suo avviso, i tradimenti occasionali della realtà oggettiva rendono le cose più interessanti sia per gli spettatori che per i creatori. Armato di questa nuova mentalità e della collaborazione di un certo membro chiave del team della seconda stagione, è partito con lo storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): i progetti di animazione. Una serie di disegni solitamente semplici che servono come sceneggiatura visiva dell’anime, disegnati su fogli speciali con campi per il numero del taglio dell’animazione, note per il rigo e le linee di dialogo corrispondenti. More e indirizza questa reintroduzione alla serie.

Se intendi valutare Shinohara, la brillante scena alla fine dell’episodio potrebbe essere il miglior esempio di ciò di cui è capace questa volta. Circondato da estroversi durante la festa di Halloween in cui è stato trascinato, Gojo è costretto ad affrontare le sue insicurezze; appartiene davvero a loro e, in realtà, appartiene a qualche posto quando i suoi interessi non sono conformi alle norme di genere? Queste paure vengono espresse attraverso un testo tempizzato con precisione mentre approfondiamo la sua psiche, mostrando la sua consueta eccellenza tecnica ma anche quel desiderio di aumentare l’astrazione. Shinohara riesce in questa nuova sfida di evocare qualcosa di più grande della realtà materiale della scena e, allo stesso tempo, gioca ancora entro i confini della sua ambientazione in modo divertente. Dopotutto, l’intera scena va avanti per minuti mentre puoi sentire Nowa cantare (piuttosto Haruhily) in sottofondo. E così, dopo essere passati dalle paure di Gojo a una piacevole sensazione di accettazione, il climax della canzone la lascia immediatamente passare a una domanda pubblica esilarante e sbagliata sul fatto che i due protagonisti si stiano frequentando. Ti benedica Nowa e ti benedica Shinohara.

80 spezzoni della scena del karaoke, comprese praticamente tutte le apparizioni di Nowa, sono stati disegnati da Hirohiko Sukegawa. Non è un caso: ha scelto il più possibile il suo personaggio preferito, estendendo i suoi compiti anche oltre lo spettacolo stesso. Il team gli ha permesso di disegnare un sacco di extra illustrazioni per accompagnare le cover di canzoni rock di Nowa (perché ha un gusto così eccezionale?) durante la seconda stagione, al punto che l’autore originale ha ripreso i suoi sforzi molto mirati. E così, mentre la stagione stava finendo, ha disegnato Nowa in modalità oshikatsu… sul vero animatore Sukegawa, che prevedibilmente ha perso la testa. Inoltre, mentre parliamo della clip sopra, il modo in cui sono elencati i nomi e le età ricorda sicuramente un’iconica scena FLCL. Sospetto che un certo assistente alla regia della serie abbia inventato questo dettaglio.

Così come il finale dell’episodio è eccellente, lo è anche l’inizio. Questa struttura è, in primo luogo, una grande mossa di adattamento. Gran parte delle prime fasi della seconda stagione si basa su piccoli cambiamenti nel flusso del materiale originale e credo che abbiano raggiunto i loro obiettivi; nel caso del primo episodio, di darci il bentornato con qualcosa che racchiuda la totalità del fascino di Kisekoi, invece di procedere come se non fosse avvenuta alcuna interruzione. E così, proprio come faceva occasionalmente il suo predecessore, la stagione 2 inizia con una parodia di genere ridicolmente divertente guidata da Kai Ikarashi, che serve anche a dire addio al defunto direttore artisticoArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): la persona responsabile della grafica di sfondo per la serie. Disegnano molte tavole da disegno che, una volta approvate dal regista della serie, servono come riferimento per gli sfondi di tutta la serie. Il coordinamento all’interno del dipartimento artistico è fondamentale: i designer dell’ambientazione e del colore devono lavorare insieme per creare un mondo coerente. Ryo Konno.

Man mano che la portata della serie si amplia, crescono anche queste divertenti anticipazioni dei suoi pezzi di narrativa nell’universo. Racchiudono più angoli della mappa otaku e diventano più concreti, soprattutto all’interno di un adattamento che li immagina molto più in là rispetto agli scorci all’interno del manga. Seguendo la penna di Ikarashi, questo diventa più… tutto. Di più. Questo è essenzialmente il modo in cui Shinohara parla del suo amico Ikarashi: qualcuno di cui ti puoi fidare non solo per capire ciò a cui alludono i tuoi storyboard, ma che poi ti supererà espandendolo ulteriormente. TsuCom è una serie dura ma sciocca che dovrebbe farti andare Dannazione, è stato divertente, ed è esattamente ciò che trasmette il lavoro di Ikarashi.

Sebbene Shinohara avesse avuto l’idea approssimativa per quella scena, è stato qualcun altro a ripulirla. uno storyboard vero e proprioStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): i progetti dell’animazione. Una serie di disegni solitamente semplici che servono come sceneggiatura visiva dell’anime, disegnati su fogli speciali con campi per il numero del taglio dell’animazione, note per il rigo e le linee di dialogo corrispondenti. Di più. Quella stessa persona gli ha fornito idee per tutta la stagione, diventando probabilmente il principale colpevole del cambiamento nel tono di Kisekoi. È finalmente giunto il momento di parlare del preferito dai fan, Yuusuke”Nara”Yamamoto, che ha assunto un atteggiamento proattivo nel suo nuovo ruolo di assistente alla regia della serie. Direttore della serie: (監督, kantoku): la persona responsabile dell’intera produzione, sia come decisore creativo che come supervisore finale. Superano il resto dello staff e alla fine hanno l’ultima parola. Esistono tuttavia serie con diversi livelli di registi: regista capo, assistente alla regia, regista di episodi della serie, tutti i tipi di ruoli non standard. La gerarchia in questi casi è uno scenario caso per caso. Come nota nell’intervista a Newtype che condivide con il suo buon amico e animatore principale Naoya Takahashi, la portata e le specifiche di quel ruolo variano notevolmente a seconda dell’ambiente e del progetto in questione. In questo caso, la portata di Nara era onnicomprensiva come normalmente lo è solo quella del leader del progetto; sempre presente fin dalle riunioni di sceneggiatura e coinvolto nelle scelte degli episodi in cui non veniva esplicitamente accreditato. Concedere a qualcuno un coinvolgimento così grande dovrebbe avere un effetto, per non parlare di un creatore con una personalità audace come quella di Nara.

In quell’intervista, Takahashi evidenzia le qualità di Nara come regista come qualcosa di unico per il suo background. Sarei ampiamente d’accordo con la sua opinione secondo cui, ogni volta che eccezionali animatori di personaggi passano a ruoli di regia, tendono a porre molta enfasi sulla bellezza e sulla solidità tecnica delle inquadrature, sull’autenticità della recitazione e sul flusso meccanico degli storyboard. Queste sono, ovviamente, qualità positive e anche un lato che Nara non ha veramente perso. Nel processo di cambiamento dei ruoli, però, è diventato un artista molto più interessato alla semplice idea di intrattenere il pubblico e coglierlo di sorpresa. Questo è qualcosa che i fan di Bocchi the Rock hanno imparato ad apprezzare molto, dato che i suoi episodi della prima stagione erano tra i meno ortodossi per quella che era già una commedia eccentrica. Tuttavia, vale la pena notare che il desiderio di sorprendere gli spettatori con una varietà di materiali è qualcosa che Nara ha mostrato in anticipo (anche in un diverso spettacolo di Bocchi!).

In un solo episodio, le ragioni che hanno permesso a Kisekoi di salire di livello così tanto sono spiegate piuttosto chiaramente. Non è una causa singolare, ovviamente. Abbiamo parlato della crescita di Shinohara, del cambiamento nel suo approccio e di come l’arrivo di Nara abbia ulteriormente alimentato entrambi. Se facciamo un passo indietro, è impossibile dissociare quest’ultimo punto dallo stato attuale della Roccia Bocchi; un limbo non pianificato che ha fatto sì che non solo il suo staff ma anche l’energia che trasportavano si riversasse su Kisekoi.

Sebbene ci sia sempre stata una sovrapposizione tra questi progetti come due serie gestite dalla banda di Umehara, il modo in cui il suo personale e il suo lato comico hanno preso il sopravvento su Kisekoi S2 parla da sé… così come il fatto che la designer di Bocchi Kerorira sia passata da animatrice occasionale a guadagnarsi la posizione di Team Support. Secondo Umehara, quel credito vuole riflettere la sua attuale posizione di qualcuno che trascende i progetti all’interno dello studio. In breve, è una figura affidabile con capacità decisionali e comunicative utili in qualsiasi momento, oltre alla sua capacità di disegnare molto.

Quando si tratta di Kisekoi S2, quel carico di lavoro più tangibile ammontava a un’apertura animata in chiave solista, assistenza agli effetti per i loro giochi nell’universo, pulizia degli episodi più pesanti e grandi porzioni di animazione chiave. Animazione chiave (原画, genga): questi artisti disegnano i momenti cruciali all’interno dell’animazione, definendo sostanzialmente il movimento senza effettivamente completare il taglio. L’industria degli anime è nota per concedere a questi singoli artisti molto spazio per esprimere il proprio stile. per concludere la stagione. Per questo primo episodio, ciò che risalta di più è la sequenza in cui una Marin piuttosto disordinata attraversa un ottovolante emotivo lasciando un po’troppo libera la sua immaginazione; quasi come se Kerorira avesse animato all’infinito una creatura rosa che lo sperimenta regolarmente. Un ringraziamento anche all’ultimo montaggio, con tutti gli altri che si accorgono del comportamento eccentrico di Marin proprio mentre un’ondata di animazione organica di sottofondo colpisce le finestre. Precisione stile Shinohara in abili mani di animazione!

Per quanto artisti come lui si distinguano, è importante stabilire che il grande aumento dei valori di produzione è onnicomprensivo e si estende oltre ogni singolo individuo. Ancora una volta, si tratta di qualcosa di strettamente legato al contesto della produzione della seconda stagione rispetto a quella precedente. Anche se non possiamo sottovalutare il fatto che CloverWorks sia in uno stato di sovrapproduzione, soprattutto perché lo studio cerca di inquadrarlo come positivo visti i risultati che ottiene, è anche innegabile che ci siano miglioramenti tangibili alla loro infrastruttura. La formazione del personale (e talvolta il bracconaggio aggressivo) ha contribuito a costruire una squadra più studiata e meglio preparata. Costruendo su quel terreno solido piuttosto che all’interno del cratere lasciato da WEP, il supporto è stato semplicemente molto più forte.

Sebbene fosse animata in chiave solista da Kerorira, l’apertura è stata diretta e con lo storyboard di Yuki Yonemori. L’affascinante integrazione dei titoli di produzione attira l’attenzione, anche se credo che il cuore della sequenza sia l’enfasi che ha posto sui materiali fisici, qualcosa della massima importanza in una serie sul cosplay. Vale la pena sottolineare che la sequenza prende in prestito molte composizioni da NO LULLABY, un video musicale che sono sicuro qualcuno ha attinto all’animazione mondiale come Yonemori ha visto molte volte. Credo che il modo in cui vengono elaborati sia trasformativo e si presenti come un cenno rispettoso, anche se sarebbe stato meglio per le persone se avessero gridato alla squadra originale. Date le regole non dette sulla menzione esplicita di altre opere, l’idea potrebbe essere stata purtroppo respinta.

Non fraintendermi, però: Kisekoi S2 ha un successo unico. Anche se credo che la divertente creatività di Bocchi lo porti ai vertici delle opere di Umehara, c’è da discutere sull’attenta precisione-non in contrasto con un’esecuzione altrettanto vivace-nella maggior parte dei Kisekoi S2, rendendola la più grande produzione di questa squadra. Lo stesso Shinohara ritiene che gli standard per episodi come la premiere della seconda stagione siano eccessivi per la televisione. Non si riferiva solo agli aspetti più visibili come i dettagli e la raffinatezza della grafica dei personaggi, o anche il grado di articolazione dell’animazione, ma anche la sontuosità degli elementi intermedi e della pittura. Il lungo tempo trascorso sugli episodi precedenti aiuta sicuramente, anche se il regista sottolinea anche che l’elevata abilità tecnica di base ha ridotto notevolmente la necessità di ripetere il film, rendendo così fattibile quel grado di ambizione. Forse, il modo migliore per descrivere il loro successo è che sembra una stagione molto ben calibrata; parte di quel segreto è che, come ha rivelato, una squadra così brava da riuscire a centrare molte cose al primo tentativo.

Questa finezza si ripercuote nel secondo episodio della stagione, che per il resto produce una notevole oscillazione tonale. Uno dei punti principali che devi comprendere per apprezzare il notevole cambiamento di sapore tra le stagioni di Kisekoi è che Nara era davvero ovunque, accompagnata da un regista della serieRegista della serie: (監督, kantoku): la persona responsabile dell’intera produzione, sia come decisore creativo che come supervisore finale. Superano il resto dello staff e alla fine hanno l’ultima parola. Esistono tuttavia serie con diversi livelli di registi: regista capo, assistente alla regia, regista di episodi della serie, tutti i tipi di ruoli non standard. La gerarchia in questi casi varia caso per caso. che era felice di assorbire le sue idee. Eppure, proprio come la concentrazione di ossigeno nell’atmosfera può variare, così può variare la densità delle particelle direttrici scandalose (vero concetto scientifico). Questi tendono ad essere al massimo, ovviamente, negli episodi che Nara ha diretto e creato storyboard personalmente, ovvero i numeri 14, 19 e 23.

Dopo la scelta della première di riorganizzare gli eventi in modo che gli spettatori venissero accolti con una dose maggiore di Kisekoiness, questo seguito ci riporta a un’avventura che avevamo saltato. I riadattamenti richiedono di mettere insieme due storie distinte, ma la consegna di Nara è così sicura che non ti lascia la sensazione che non ci fosse una visione chiara dietro. Certo, passiamo dalla continuazione della commedia romantica sul fatto che stiano uscendo insieme al cosplay e alle trame incentrate sul genere, ma entrambi sono trasmessi attraverso mix di stili altrettanto eclettici.

Nara è sempre disposta a passare dalla normalità radicata di Kisekoi a i suoi ricordi che l’animazione è composta da risorse che lui può giocare con. C’è quel familiare senso della commedia costruito su rapidi cambiamenti stilistici ogni volta che riesce a trovare un modo per intrufolarlo; cambiare i livelli di stilizzazione, di fluidità nell’animazione e poi sovvertire le tue aspettative da un vettore completamente nuovo quando pensi di aver rotto lo schema. Proprio come nell’anime di Bocchi che episodi come questo tanto ricordano, è il costante senso di sorpresa che diventa il collante tra parti eterogenee.

Visto che abbiamo parlato della sequenza d’apertura, dovremmo introdurre anche il finale. La sequenza finale di VIVINOS ricorda molto la loro serie Pink Bitch Club, prendendo la cotta di Marin e il suo interesse per la moda come scusa per trasformarla in una sorta di minaccia menhera.

Se ci fermiamo e apprezziamo l’animazione, ancora una volta eccellente, possiamo trovare moltissimi esempi di combinazioni di idee apparentemente inquietanti che portano a un risultato più ricco. Con un regista così veloce nell’abbracciare l’estetica fumettistica, si potrebbe presumere che questa sia la strada che seguirà ogni volta che ci saranno esigenze comiche, ma Nara guida con successo la squadra per ottenere il massimo da approcci meno comuni. Come, ad esempio, aumentare leggermente il realismo per rendere una sequenza più divertente. As an embarrassed Marin storms away from Gojo, the level of lifelike detail in which the folds of his disguise are depicted—a bit exaggerated but not so much that they become a caricature—makes him look much creepier and thus funnier in this context. Even when the application of a style is more orthodox, the ability to alternate between them will keep you constantly engaged. After all, the same visit to a sick Marin can have outstanding examples of precision in animation and inherently funny betrayals of space. In a season with many outrageous visual tricks, even the seemingly more standard sequences can be inherently fun to look at.

One detail we’ve neglected to mention is that all those scenes arrived by the hand of the aforementioned main animator, Naoya Takahashi. Speaking to Newtype, he simplified the evolution of his role as going from a tactically deployed weapon across important moments in the first season, to handling large chunks at a time for the sequel. This is not to say that he no longer handled climactic moments, since we’re talking about an animator with a hand in the very last scene of the season. However, it’s true that he halved his appearances so take he could take over many cuts whenever he showed up as either key animator or supervisor.

Applied to episode #14, that meant drawing key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. for virtually every single shot in the first half; the only small exceptions being Odashi and the regular Yohei Yaegashi making cute guest appearances, in rather different ways. Nara is particularly effusive about Takahashi’s mindset, as an animator whose interests are tickled by seemingly troublesome cuts that he’ll complicate even further, but it’s worth noting that the entire second half received the same holistic treatment by Maring Song. Given that its animation demands are just as diverse, the challenge couldn’t have been any easier.

Even with those assistants and the help of a solid lineup of 2nd key animators, having the episode’s two animation directors penning every single cut in the first place is quite the ask. And keep it in mind: it was an ask, not a spur-of-the-moment happening but a foundational idea in planning Kisekoi S2. Those Newtype features confirm as much, saying it was an episode conceived to be animated by a small team. While this one is noteworthy in how far they went with it, the desire to keep animation teams small is a defining trait of Umehara’s production line in recent times. From a creative standpoint, there’s an obvious reason to chase that goal: the natural sense of cohesion and full realization of a better-defined vision that you can get out of small teams. And from a management level, the idea that you may be able to offload this large a workload to just a few people—at least for certain tasks—is a dream come true.

While it’s positive that viewers have started paying attention to the composition of teams (who is part of them, their size, roles, etc), many are a bit too quick to assume that seeing fewer animators credited is immediately a sign of a healthier, straight-up superior production. Instead, they should be asking themselves if such a team was a natural fit for the production circumstances, and whether the level of ambition and quality standards match their possibilities.

Circling back to Kisekoi S2, then, we can say that episodes like this manage to maintain—and occasionally even raise—the project’s already impressive technical floor despite the small team. And what about the larger picture? Did this approach eventually push the production off the rails? Although things got tighter by the end, we can now say that it weathered the storm without requiring the level of unthinkable individual feats that protected the likes of Bocchi. In that regard, it’s worth noting that Kisekoi S2 showed an interesting level of restraint. Small teams of animators, but never as far as this one episode. A mere two episodes with a singular animation director, instead opting for duos as its default. Part of this comes down to the improvement of CloverWorks’ infrastructure (not to be confused with their planning) that we talked about earlier, but it’s also about that evolution in Umehara’s mindset; away from his most aggressive tendencies, less allergic to the concept of compromising, and instead interested in finding ways to minimize the negative effects from that.

It’s another one of Umehara’s favorite weapons that takes over the show with the next episode: character animation ace Tomoki Yoshikawa, who makes his debut as storyboarder and episode director. If his peers viewed Nara as a very entertaining aberration, Yoshikawa embodies straightforward excellence in his breed. As an animator, Yoshikawa’s work feels performed in a way that few artists’ do; so specific in its posing and demeanor that you feel as if the characters were actors who’d just been briefed by the director. And now that he genuinely occupies that position, you get that philosophy applied to an entire episode—often through his own redraws. The way people interact with objects and people’s gestures constantly stand out as deliberate. The way he accomplishes it makes his ostentatious brand of realism not particularly naturalistic, but its technical greatness and sufficient characterfulness justify its braggadocio air. Perhaps this is the horseshoe he shares with Nara: one, a director so imaginative that he gets away with making the artifice painfully obvious, the other, an animator so good at articulating characters that he’s happy with showing you the strings with which he puppeteers them.

Despite yet another charismatic lead artist having a visible impact, Kisekoi S2’s overarching identity is too strong to ever disappear. Instead, what happens is that the two tendencies tend to mix with each other. Yoshikawa’s deliberate acting doesn’t risk coming across as too clinical and serious, as his precise posing occasionally becomes a source of humor as well; for an obvious example, a binoculars-like shot is followed up by the type of silly pose that Marin is likely to adopt when her nerdy side takes over. The switches to blatantly cartoony animation can occur without ditching the calculated staging, and for that matter, without ditching Yoshikawa’s pen either—he personally key animated some of them as well.

The real highlight of the episode, though, is in Amane’s backstory. At this point, it should be obvious that Yoshikawa is more than a cold, technically proficient animation machine. He once again shows that much with a stunning flashback focused on the main duo’s new friend and his encounter with crossplay, which helped him forge an identity he’s finally comfortable with. Through some of the most ethereal drawings in the entire show (many by Yoshikawa himself), we witness his first experiences with makeup, wigs, and dresses. We see neither his face nor reflection, but it quickly becomes obvious that it’s because his past, regular self was one that he’d never been comfortable with. It’s impossible not to feel the contrast with his current persona, highlighted by all the cuts to the present clearly showing a happy face after so much obscuration of his expressions. The Amane of right now, the person cosplaying a female character while hanging out with Marin and Gojo, is the self that he loves and proudly projects outward.

This type of conflict is by no means new to Kisekoi. After all, Gojo’s own insecurities are also rooted in traumatic rejection over his gendered interests; and of course, Marin being a widely beloved, popular girl with some very male-coded hobbies is the flipside to his situation. Up until now, though, none of those situations had been presented in such striking fashion. If we add to that the way that Kisekoi’s exploration of otaku spaces widens—and this is only the beginning—the message of acceptance that had always been attached to the series starts feeling more meaningful.

The following episode ventures further in that regard. Although it’s the first chance for the production to take a bit of a breather, one aspect took a lot of work and it very much shows: the depiction of PrezHost. As is the norm with this season, an in-universe work briefly depicted in the manga becomes a fully fledged production effort within its anime adaptation. The beautiful designs by WEP’s Saki Takahashi and the evocative compositions it dashes out when necessary sell the appeal of the series, though it’s the concept itself that feels most important.

Even though Kisekoi rejects conforming to the preconceptions about what individuals ought to enjoy according to their age or gender, constantly doing so while only ever portraying danseimuke fiction (or types of work otherwise largely tolerated by men) would make its plea for acceptance ring rather hollow. This makes their fancy depiction of a shoujo manga turned popular live-action drama such a great choice, because it feels like it understands what teenage girls and families alike—including some boys, awkward about it they are—would get really into. I have to admit that, given the extremely obvious Ouran vibes of this fake series, I’d have loved to see much more overt mimicry of Takuya Igarashi’s direction; at best, Mamoru Kurosawa’s storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime’s visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. More and its SHAFT flavor merely evoke vibes that feel like a distant stylistic cousin. That said, beautiful animation dedicated to something that strengthens your whole series’ message is hardly a reason to complain.

Between WEP’s early moments of excellence and his work across the 22/7 short films, Wakabayashi earned himself a reputation as a breathtaking director, the type that invites you into ethereal spaces where mundanity feels divine. Mind you, there is still plenty of room for delicacy and elegance across his boards here. Within an arc that strongly emphasizes collective work and the reliance on everyone’s specific skills, episode #17 allows the fundamentally subdued animation to do the talking; Gojo’s expert movements contrast with Marin’s well-meaning flubs, yet she’s the one who irradiates confidence with her body motion when she’s in her field. The intricacies of seemingly mundane animation tell us a lot, just by swinging from one of Marin’s beastly lunches to Gojo’s delicate eating as drawn by Shinnosuke Ota. Even that otherworldly vibe of Wakabayashi’s direction is channeled through the depiction of light, dyeing the profiles of the lead characters when they’re at their coolest and most reflective.

However, those are merely the gifts that you’ll find hidden within the bushes—or rather, in a very exuberant, colorful jungle. Wakabayashi and episode director Yuichiro Komuro, an acquaintance from WEP who already did solid work in Kisekoi S1, meet this sequel on its own terms. Stronger comedic edge, but also the incorporation of different genres we hadn’t explored before? Playful emphasis on the farcicality of animation assets, as well as a much higher diversity of materials? If that is the game we’re playing now, Wakabayashi will happily join everyone else. And by join, I mean perhaps best them all, with a single scene where Marin squeals about her crush being more densely packed than entire episodes; horror buildup, an imaginative TV set, slick paneling that breaks dimensions and media altogether, and here’s a cute shift in drawing style as a final reward. Wakabayashi may be playing under someone else’s rules, but he’s far from meek in the process. Episode #17 is out and proud about being directed, with more proactive camerawork than some hectic action anime and noticeable transitions with a tangible link to the narrative.

For as much as episodes like this rely on the brilliance of a special director, though, this level of success is only possible in the right environment. This is made clear by one of the quirkiest sequences: the puppet show used for an educational corner about hina dolls. The genesis is within Wakabayashi’s storyboards, but the development into such a joyful, involved process relied on countless other people being just as proactive. For starters, the animation producer who asked about whether that sequence would be drawn or performed in real life, then immediately considered the possibility of the latter when Wakabayashi said it could be fun. There’s Umehara himself, who’d been watching a documentary about puppeteer Haruka Yamada and pitched her name. The process this escalated into involved all sorts of specialists from that field, plus some renowned anime figures; no one better than Bocchi’s director Keiichiro Saito to nail the designs, as dolls are an interest of his and he has lots of experience turning anime characters into amusing real props. Even if you secure a unique talent like Wakabayashi, you can’t take for granted the willingness to go this far, the knowledge about various fields, and of course the time and resources required for these side quests.

And yet, it’s that emphasis on clinical forms of animation that also makes it feel somewhat dispassionate—especially after the playfulness of Wakabayashi’s episode. The delivery is so fancy that it easily passes any coolness test, and it certainly has nuggets of characters as well; watching the shift in Marin’s demeanor when she’s performing makes for a very literal, great example of character acting in animation. But rather than leaning into the fun spirit of a school festival, the direction feels very quiet and subservient to an artist who can lean towards the mechanical. It’s worth noting that the most evocative shots in the entire episode, which break free from its cold restraint, come by the hand of Yusuke Kawakami. Those blues are a reminder of the way he already stole the show once, with that delightful eighth episode of the first season.

Kisekoi S2 is certainly not the type of show to dwell in impassionate technicality for too long, so it immediately takes a swing with another fun episode captained by Nara. A leadership that this time around doesn’t merely involve storyboarding and direction, but even writing the script as well. Given that the animation director is Keito Oda, it ends up becoming quite the preview for the second season of Bocchi that they’re meant to lead together. His touch can be felt through the spacious layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. and the character art itself, with scenes like the one at the karaoke feeling particularly familiar. A noticeably softer feel within a series where the designs normally lean in sharper directions.

Even though Nara mostly plays with regular tools for this episode, the same eclecticism we’ve been praising so far is all over the episode. At no point can you be sure about which technique, palette, and type of stylization he’s going to deploy when depicting Marin’s struggles. This helps spice up an episode that is otherwise a simple breather. Weight gain scenarios in anime rarely lead to a fun time; you don’t have to start considering whether they’re problematic or not to realize that they’re formulaic and repetitive. However, within a show where bodies are meaningfully explored and thanks to Nara’s amusing resourcefulness, it becomes yet another entertaining episode.

Additionally, there is a reason why we said that the director mostly uses regular tools in episode #19. The highlight is a sequence built upon a 3D scan of a real park, in a process that took 9 months to complete. Although there are technical points of friction like Marin’s lack of a projected shadow, this was a tremendous amount of effort applied to a fundamentally compelling idea. Within regular comics, a sudden switch to a series of identical panel shapes feels unnatural. In the context of a series about cosplay, that’s enough to tell that someone is taking photos. But what about anime (and more broadly, film) where the aspect ratio is consistent? A solution can be to reimagine the whole sequence as a combination of behind-the-camera POV and snapshots that don’t reject the continuity.

While on the surface it might seem like a more modest showing, episode #20 is—in conjunction with the next one—a defining moment of Kisekoi S2. Director and storyboarder Yuuki Gotou is still a bit of a rookie in this field, but may prove to be one of the best scouting moves for the team. Alongside the small changes in the script, the direction toys with the themes of the series in a way that casually solidifies the entire cast. Gojo and Marin attend a cosplay event and come across acquaintances, including multiple friend-of-a-friend scenarios. Those involve someone who, in the manga, is merely mentioned as having been too busy to attend. In the end, we don’t know much about her, and she doesn’t even register as a person. What does Gotou’s episode do, though? It transforms the manga’s plain infodumping about cosplay culture into a fake program that stars her as the host, which makes the eventual reveal that she couldn’t show up more amusing and meaningful; now she actually is a person, albeit a pitiful one. The delivery of the episode is enhanced by similar small choices, in a way that is best appreciated if you check it out alongside the source material.

The immediate continuity in the events links that episode to #21, which also underlines the essence of season 2’s success. I’m sure we’ve all witnessed discourse about anime’s self-indulgent focus on otaku culture at some point. The very idea of acknowledging its own quirks and customs is framed as an ontological evil, though really, those complaints amount to little more than cheap shots at easy targets that people can frame as progressive, refined stances. Were they truly that thoughtful about cartoons, people would realize that such anime’s common failing isn’t the awareness and interest in its surrounding culture—it’s the exact opposite. Anime isn’t obsessed with otaku, but rather with going through familiar motions and myopically misrepresenting a culture that is much broader than we often see. Every late-night show that winks at a male audience about tropes they’ll recognize is blissfully unaware of the history of entire genres and demographics; and for that matter, about the ones that it’s supposed to know as well, given how many gamified Narou fantasies fundamentally don’t understand videogames.

Due to Marin’s choices of cosplay and the unbalanced presentation of the first season, Kisekoi risked leaning a bit in that direction as well. But with a series that genuinely wants to engage with the culture it explores, and a team willing to push its ideas even further, that simply couldn’t come to pass. The most amusing example of this across two episodes is Marin’s cosplay friends, as women who feel representative of distinct attitudes seen in female otaku spaces. From the resonant ways in which proactive fandom is linked to creative acts to the jokes they make, there’s something palpably authentic about it. Nerdy women don’t morph into vague fujoshi jokes, but instead showcase highly specific behaviors like seeing eroticism in sports manga that read completely safe to people whose brains aren’t wired the same way. Kisekoi S2 gets a lot of humor out of their exaggerated antics—both #20 and #21 are a riot about this—but these are just one step removed from real nerds you wouldn’t find in many anime that claim to have otaku cred.

This exploration continues with the type of fictional works that motivate their next cosplay projects. Just like PrezHost felt like a spot-on choice for a group of regular teenagers, an indie horror game like Corpse is perfect for this nerdier demographic of young adults and students; if you wanted to maximize the authenticity, it should have been a clone of Identity V as that was a phenomenon among young women, but their slight departure still becomes a believable passion for this group. And most importantly, it looks stunning. Following the trend you’ve heard about over and over, a loosely depicted in-universe game becomes a fully-fledged production effort led by specialists—in this case, pixel artist narume. It’s quite a shame that, no matter how many times I try to access the website they made for the game, it doesn’t become something I can actually play.

The purposeful direction of Haruka Tsuzuki in episode #21 makes it a compelling experience, even beyond its thematic success. Though in a way, its most brilliant scene is still tied to that—Marin’s subjectivity being so clearly depicted is one of the ways in which Kisekoi pushes back against common failings of the genre, after all. When she misunderstands what Gojo is buying, diegetic green lights flash green, like a traffic light signaling his resolve to go ahead. Marin’s panic over the idea of getting physically intimate coincides not just with a camera switch to show an adults-only zone of the store nearby, but also with the lights turning red. She doesn’t exactly feel ready… but the more she thinks about it, the lights switch to pink. If I have to explain what this one means, please go ask your parents instead.

Season 2 thrives because of this broader, deeper depiction of cosplay as an extension of otaku culture. As we mentioned earlier, it makes the message of acceptance feel like it carries much more weight; with a palpable interest in more diverse groups of people, the words of encouragement about finding your passions regardless of what society expects you to do have a stronger impact. Since the preceding season faltered by focusing on arcs where these ideas were still raw, while also introducing biased framing of its own, there’s a temptation to claim that Kisekoi S2 is superior because it stuck to the source material even more. And let’s make it clear: no, it did not. At least, not in those absolute terms.

There is an argument to be made that it better captures the fully-developed philosophy of the source material; the argument is, in fact, this entire write-up. That said, much of our focus has also been on how Shinohara’s desire to increase the expressivity and the arrival of Nara have shifted the whole show toward comedy. Kisekoi has always had a sense of humor, but there’s no denying that this season dials up that aspect way beyond the source material. That has been, as a whole, part of the recipe behind such an excellent season.

And yet, we should also consider the (admittedly rare) occasions where it introduces some friction. If we look back at episode #20, one of the highlights in Gotou’s direction is the goofy first meeting between Akira and Marin. Since we’re taking a retrospective look after the end of the broadcast, there’s no need to hide the truth: Akira has a tremendous crush on her. However, their entire arc is built upon everyone’s assumption that she hates Marin, as she gets tense and quiet whenever they’re together. The manga achieves this through vaguely ominous depictions of Akira, which would normally be read as animosity but still leaves room for the final punchline. The adaptation mostly attempts to do the same… except their first meeting is so comedic, so obvious in the falling-in-love angle, that it’s impossible to buy into the misdirection. Every now and then, it’s in fact possible to be too funny for your own good.

If we’re talking about the relative weaknesses of the season, episode #22 is a good reminder that outrunning the scheduling demons—especially if you enjoy taking up creative strolls to the side—is hard even for blessed projects. Conceptually, it’s as solid as ever. Marin’s sense of personhood remains central to everything, with her own struggles with love and sexuality being as carefully developed (if not more) than anything pertaining to Gojo. Being treated to another showcase of Corpse’s beautiful style is worth the price of admission, and you can once again tell that Fukuda understands nerds as she writes them salivating over newcomers’ opinions on their faves. It is, though, a somewhat rougher animation effort despite all the superstars in various positions of support. While the decline in quality is only relative to the high standards of Kisekoi S2, seeing what caliber of artist it took to accomplish an acceptable result speaks volumes about how tight things got.

Thanks to the small structural changes to the adaptation, this episode is able to reinforce the parallels between Akira’s situation and the world’s most beloved cosplayer Juju-sama (sentence collectively written by Marin and her sister). Sure, Juju’s got a supportive family and has been able to chase her dreams since an earlier age, but there have always been hints that she holds back somewhat. As a cosplayer with utmost respect for the characters, she never dared to attempt outfits where her body type didn’t directly match that of the original. This is why we see similar framing as that of a student Akira, feeling cornered before she stumbled upon a space to be herself. Nara may be an outrageous director, as proven by how quickly he unleashes paper cutout puppets again, but you can see his a subtler type of cheekiness in his storyboards as well; cutting to Juju’s shoes with massive platforms during a conversation about overcoming body types is the type of choice that will make you smile if you notice it.

On top of that thematic tightness and meaningful direction, episode #23 is also an amazing showcase of animation prowess. Separating these aspects doesn’t feel right in the first place; the compelling ideas rely on the author’s knowledge about the specifics of cosplay, which are then delivered through extremely thorough and careful animation. The likes of Odashi and Yuka Yoshikawa shine the best in that regard, though it’s worth noting that the entire episode is brimming with high-quality animation—and most importantly, with respect for the process of creating things as an expression of identity. Be it the Kobayashi-like acting as Juju storms out during a pivotal conversation about that, or a familiar representation of cosplay as a means to reach seemingly impossible goals by Hirotaka Kato, you can never dissociate the episode’s beautiful art from its belief that making things can allow us to be our real selves.

Again, it’s no secret that an episode like #23 was produced under strict time constraints; perhaps not in absolute terms, but very much so when you consider its level of ambition. In the context of not just this series but the production line we’ve been talking about all along, what’s interesting isn’t the achievement itself, but how it relates to an evolution we’ve observed before. Umehara’s more considered stance and CloverWorks’ improving infrastructure have been recurring themes, but there’s been one key piece of information relating to both that we’ve been keeping a secret. For as much as we’ve referred to this team as Umehara’s gang, which it very much is, you may have noticed that earlier we talked about a separate animation producer—the position that Umehara held in previous projects. So, what happened here?

As he has alluded to on Twitter but more extensively talked about in his Newtype interview, Umehara is not just aware of CloverWorks’ changes, but also quite hopeful about its up-and-coming management personnel. In his view, most of them are just one piece of advice away from figuring out the tricks to create excellent work. And yet, being the animation producer, he tends to be too far from the trenches for those less experienced members to come to him for advice… unless things have gotten really dire. That is, to some degree, simply not true; Umehara is too emotionally invested in the creative process to separate himself from it, no matter what his position at the company is. However, it’s correct that production assistants are more likely to go to their immediate superior rather than someone two steps above when they’ve simply got some doubts. And thus, Umehara has been the production desk for Kisekoi S2, whereas Shou Someno has replaced him in the producer chair.

The first-hand advice Umehara has been able to give will surely be meaningful for the careers of multiple production assistants. And just as importantly, Kisekoi S2 has been an excellent lesson for him. Right after the broadcast of episode #23, and even acknowledging the lack of time, Umehara expressed his delight about what the team had accomplished for the one episode where he was not at all involved in the management process. That future he dreamed of, where the quality of his production line’s output could be maintained without his constant presence, has finally come. Chances are that it could have come faster and less painfully if he hadn’t been so afraid of delegation before, if this team’s well-meaning passion had been channeled in more reasonable ways. Whatever the case, this feels like a positive change if we intend to balance excellent quality with healthier environments… as much as you can within the regime of a studio like this, anyway.

Our final stop is an all-hands-on-deck finale, with Shinohara being assisted by multiple regulars on the team. Though they all made it to the goal with no energy to spare, the sheer concentration of exceptional artists elevates the finale to a level where most people would never notice the exhaustion. The character art retains the polish that the first season could only sniff at its best, and the animation is thoroughly entertaining once again; a special shout-out must go to Yusei Koumoto, who made the scene that precedes the reveal about Akira’s real feelings for Marin even funnier than the punchline itself.

More than anything else, though, the finale shines by reaping the rewards of all the great creative choices that the season has made beforehand. In contrast to the manga, where Corpse was drawn normally, having developed a distinct pixel art style for it opens up new doors for the adaptation. The classic practice of recreating iconic visuals and scenes during cosplay photoshoots is much more interesting when we’re directly contrasting two styles, each with its own quirks. The interest in the subject matter feels fully represented in an anime that has gone this far in depicting it, and in the process, likely gotten more viewers interested in cosplay and photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process.. Perhaps, as Kisekoi believes, that might help them establish an identity they’re more comfortable with as well.

Even as someone who enjoyed the series, especially in manga form, the excellence of Kisekoi S2 has been truly shocking. I wouldn’t hesitate to call it the best, most compelling embodiment of the series’ ideas, as the lengths they went to expand on the in-universe works have fueled everything that was already excellent about Kisekoi. It helps, of course, that its series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. Superano il resto dello staff e alla fine hanno l’ultima parola. Esistono tuttavia serie con diversi livelli di registi: regista capo, assistente alla regia, regista di episodi della serie, tutti i tipi di ruoli non standard. La gerarchia in questi casi varia caso per caso. has grown alongside the production line, especially with the help of amusing Bocchi refugees. Despite a fair amount of change behind the scenes and the exploration of more complex topics, the team hasn’t forgotten they’re making a romcom—and so, that stronger animation muscle and more refined direction also focus on making the characters cuter than ever. Given that we’re sure to get a sequel that wraps up the series altogether, I can only hope we’re blessed with an adaptation this inspired again. It might not dethrone Kisekoi S2, but if it’s half as good, it’ll already be a remarkable anime.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. I fan occidentali si sono appropriati da tempo della parola per riferirsi a casi di animazione particolarmente buona, allo stesso modo di un sottogruppo di fan giapponesi. Abbastanza integrante del marchio dei nostri siti. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. I fan occidentali si sono appropriati da tempo della parola per riferirsi a casi di animazione particolarmente buona, allo stesso modo di un sottogruppo di fan giapponesi. Abbastanza integrante del marchio dei nostri siti. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()