My Dress-Up Darling/Kisekoi a toujours été charmant, mais il a atteint un nouveau niveau avec une suite plus créative, plus thématique et, ce faisant, plus diversifiée dans les sous-cultures qu’elle explore. Examinons les changements de production qui ont si extraordinairement bien porté leurs fruits !

La première saison de My Dress Up Darling/Sono Bisque Doll wa Koi wo Suru, que nous appellerons Kisekoi pour nous épargner cette bouchée de titre, était une adaptation tout à fait raisonnable d’une série agréable. Il s’agissait cependant d’une synthèse un peu réductrice de ce que l’œuvre originale englobe. Attention, ce n’est pas toujours un aspect négatif, encore moins un facteur décisif. Au contraire, on pourrait dire qu’il est naturel que les adaptations se manifestent ainsi ; il est beaucoup plus facile de concevoir une expérience étroitement ciblée en prévoyant des publications en cours ou même terminées depuis longtemps, alors que les auteurs originaux qui viennent tout juste de commencer leur travail luttent avec l’inconnu. Certaines séries ont été manifestement améliorées grâce à leurs adaptations à cause de cela, que ce soit en supprimant des éléments qui, rétrospectivement, étaient mal adaptés, ou grâce à de simples choix d’accentuation.

En ce qui concerne Kisekoi, cependant, je ne crois pas que ce soit le cas. Encore une fois, ne prenez pas cela comme une critique sévère de sa première émission télévisée, qui était globalement solide. Quiconque l’a vu peut attester que sa prestation allait de techniquement solide à parfois exceptionnelle, avec des normes d’animation confortablement supérieures à la norme des anime télévisés actuels. Et pourtant, l’arrivée de sa suite démontre l’existence d’un potentiel plus large qu’ils n’avaient pas pu exploiter du premier coup.

La relative étroitesse de la saison 1 a commencé avec un aspect que l’on peut difficilement reprocher à l’équipe créative: le nombre d’épisodes. Disposant d’un seul parcours, l’équipe a fait le meilleur choix qui s’offrait à elle et a avancé à un rythme mesuré, même si cela ne lui a pas permis d’atteindre les arcs (les plus récents à l’époque) où le manga prend véritablement son essor. Bien que toujours agréable, le travail de Shinichi Fukuda met un certain temps à s’élever d’une comédie romantique mignonne qui énonce un message qui sonne bien, à une comédie où ces croyances résonnent à chaque page avec le type de conviction à laquelle on ne peut s’empêcher d’adhérer.

En termes plus spécifiques, cela signifie que la série élargit progressivement ses horizons dans sa représentation du cosplay et de la culture otaku dans son ensemble. Son respect pour les premiers ne pourrait jamais être remis en question ; plusieurs chapitres de la série, y compris les étapes précédentes, sont si complets dans leur description du passe-temps qu’ils pourraient servir de didacticiels. Cela s’est également traduit dans la première saison de l’anime, offrant un regard incontestablement affectueux sur la sous-culture… ou plutôt, dans la tranche de celle-ci présente dans le matériel qu’ils auraient le temps de s’adapter. C’était suffisant pour faire preuve d’idées telles que le fandom proactif et la création dérivée comme moyens précieux de canaliser votre amour, ainsi que pour repousser la pression sociétale sur ce que nous devrions aimer. Bien que ce soient des thèmes qui accompagnent naturellement Gojo et Marin tout au long de leur romance naissante, ils ne sont pas encore complètement formés à ce stade. Les concepts semblent quelque peu détachés des points forts de la production, et tout simplement pas du tout liés aux réalités de la plupart des gens au sein de la culture qu’ils explorent. Ces thèmes sont, en bref, une vitrine adéquate pour une jolie comédie romantique.

Dans une certaine mesure, cette étroitesse de saveur se résume à l’exécution. Si je vous dis de fermer les yeux et d’imaginer quelques séquences mémorables de la première saison, je sais pertinemment qu’une combinaison de représentation rebondissante et volumétrique du corps de Marin dans des vêtements étriqués vous est venue à l’esprit. Il ne s’agit pas ici d’une tentative de faire honte aux pervers parmi nos lecteurs: dans les sites destinés à l’appréciation de l’art, la perversion est avant tout une sorte d’insigne d’honneur. Ce que je veux dire, cependant, c’est que ces séquences ont reçu un niveau de diffusion mémorable et clairement exceptionnel que la série ne pouvait pas se permettre de manière régulière. C’est une inégalité dans la valeur d’impact (même si le sol est toujours respectable) qui donne la fausse impression que ces moments sont tout ce dont parle la série.

Il convient de noter que, lorsque l’on revient sur la première saison pour une série d’interviews de Febri, la série réalisateurRéalisateur de série : (監督, kantoku) : la personne en charge de l’ensemble de la production, à la fois en tant que décideur créatif et superviseur final. Ils surpassent le reste du personnel et ont finalement le dernier mot. Il existe cependant des séries avec différents niveaux de réalisateurs: réalisateur en chef, assistant réalisateur, réalisateur d’épisodes de série, toutes sortes de rôles non standards. La hiérarchie dans ces instances est un scénario au cas par cas. Keisuke Shinohara a admis avoir initialement supposé que Kisekoi n’était qu’un régal pour les yeux des hommes. Ce n’est qu’en poursuivant sa lecture qu’il s’est senti profondément attiré par les luttes de Gojo en tant que créateur ; bien qu’il soit dans des domaines différents, il a trouvé que son arc résonnait auprès de tous ceux qui s’investissaient dans la création de choses. C’est également en approfondissant la série qu’il en est venu à apprécier la représentation des sentiments de Marin d’une manière précise, tout aussi importante – un contraste avec la tendance des comédies romantiques danseimuke qui présente les femmes comme des objets de poursuite inconnaissables. Cela semble être un sentiment partagé au sein de l’équipe, puisque le producteur en chef d’Aniplex Nobuhiro Nakayama a récemment fait référence à l’énergie de type shoujo de la série à cause de cela.

Cela dit, il y a plus d’aspects dans la série ne signifie pas que l’érotisme n’a pas a toujours fait partie de Kisekoi. Nous suivons deux adolescents, chacun sous son angle de maladresse, qui tentent de comprendre leur sexualité. L’une d’elles a suffisamment confiance en son corps pour tenter de cosplayer des personnages provocateurs de jeux pour adultes ; mettant en avant le rapport entre une série sur ce thème et la représentation des corps, ainsi que le fait qu’elle aime beaucoup les jeux pornographiques. Et, ce qui est sans doute le plus important, Fukuda ne cache pas qu’elle aime représenter Marin de manière sexy. Compte tenu de cette prémisse et de l’accès de l’équipe à quelques artistes de personnages exceptionnels qui se feront un plaisir de tout mettre en œuvre sur ces séquences, ce n’est ni une surprise ni un inconvénient que de nombreux moments forts de la première saison correspondent à des coupes racées de Marin. Si nous jugeons uniquement l’exécution, le problème réside davantage, que ce soit en raison de la perception ou d’une relative faiblesse, des autres côtés de Kisekoi S1 qui n’ont pas frappé avec la même force.

Pour commencer, il est important de se rappeler le contexte de la production de cette première saison. Bien que bien conçu pour les standards des anime télévisés, nous ne pouvons pas oublier qu’il a suivi l’implosion absolue de Wonder Egg Priority. Bien que l’ambition de Shouta Umehara en tant que producteur d’animation alimente ce qui est sans aucun doute l’équipe la plus prestigieuse de CloverWorks, il en a parfois exagéré au point de devenir également gênant. Ce n’est en aucun cas un leader cruel qui exploite les autres, mais plutôt un type téméraire qui mène même des missions suicidaires ; n’oubliez pas que la personne que WEP a envoyée à l’hôpital était lui-même. Son attitude à l’époque a évolué progressivement – d’une manière qui affectera plus tard la deuxième saison de Kisekoi – mais plus que toute autre chose, c’est cet épuisement mental et physique post-WEP qui a ramené les standards de leur prochain projet sur terre. La première saison de Kisekoi a accepté un seuil plus bas de cohérence et de qualité pour l’art des personnages et, de manière assez notoire, comportait deux épisodes entièrement sous-traités (#03 à Traumerei Animation Studio et #07 à Lapin Track). C’est une production solide, mais aussi la définition même de la retenue. Dans ce contexte, c’est compréhensible.

Une autre raison pour laquelle les plans occasionnels de Marin se sont démarqués par-dessus tout le reste, et la raison pour laquelle nous avons introduit l’idée de perception plus tôt, est que le directeur de la série. Directeur de la série: (監督, kantoku): la personne en charge de l’ensemble de la production, à la fois en tant que décideur créatif et superviseur final. Ils surpassent le reste du personnel et ont finalement le dernier mot. Il existe cependant des séries avec différents niveaux de réalisateurs: réalisateur en chef, assistant réalisateur, réalisateur d’épisodes de série, toutes sortes de rôles non standards. La hiérarchie dans ces instances est un scénario au cas par cas. Shinohara est discret par nature. Le début de la première saison était déjà suffisant pour illustrer que, même lorsqu’il utilise l’exagération, il le fait d’une manière tellement calculée qu’on prend pour acquis son interprétation convaincante. Par sa technique et son esprit, il utilise sa position de réalisateur pour protéger l’immersion du spectateur de tout éclatement. Il n’est peut-être pas un réaliste strict, mais il a le type de vision ancrée qui l’oblige à représenter des projecteurs figuratifs de la même manière que vous montreriez de vraies lumières. Bien qu’il n’ait jamais mis de côté le sens de l’humour de l’œuvre originale, ce sont d’autres réalisateurs d’épisodes de la première saison qui se sont appuyés plus ostensiblement sur celui-ci. Surtout à l’époque, Shinohara était heureux de viser un sentiment de transparence ; être authentique dans la représentation des personnes et du sujet, laissant l’artifice aux autres.

En ce qui concerne cette première saison, des épisodes comme le n°11 ont offert le type de friction auquel Shinohara est plus naturellement opposé ; suivant l’exemple d’un certain réalisateur qui a ensuite été mis à l’avant-garde de la suite, il a montré un Kisekoi plus effronté qui était prêt à jouer avec la nature farfelue des personnages comme des actifs 2D avec lesquels vous pouvez jouer. Mais, sous un tout autre angle, le véritable point culminant a été le huitième épisode mené par Yusuke Kawakami. Au début, une longue scène animée par Kerorira présente le type de représentation charismatique des draps que nous ne voyons autrement que dans les scènes épicées de la saison 1. Au fur et à mesure que vous vous aventurez plus loin dans l’épisode, la représentation d’une série de filles magiques plus âgées fait des concessions à l’authenticité en faveur de la règle du cool. Une atmosphère beaucoup plus palpable que celle que vous rencontrez dans le reste de la série oscille entre terreur et vulnérabilité lorsqu’un personnage s’ouvre à Gojo, puis passe tout aussi rapidement à des des hijinks visuels hilarants.

Contrairement à la discrétion de Shinohara, le storyboard de KawakamiStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte) : Les plans de l’animation. Une série de dessins généralement simples servant de script visuel à l’anime, dessinés sur des feuilles spéciales avec des champs pour le numéro de coupe de l’animation, des notes pour la portée et les lignes de dialogue correspondantes. More est du genre à vous arrêter fièrement dans votre élan. Il existe un sentiment d’élégance partagé qui lui permet d’exister dans le cadre du réalisateur de la série, mais l’exécution est beaucoup plus ostentatoire et manifeste. Ne cherchez pas plus loin que la percée de Juju sur son identité et ses rêves, véhiculée par un chevauchement clair de son reflet et d’une tenue de fille magique. L’ensemble du segment final avec Marin et Gojo sur la plage est une représentation éthérée des premières ; du premier amour, des premières sorties à la plage et de la première fois qu’une mouette vous manque de respect, car cela reste idiot même avec ces vibrations surnaturelles que Kawakami et le reste de l’équipe lui ont accordées. L’épisode présente, de haut en bas, un savoir-faire exceptionnel et une prestation tout à fait mémorable au cours d’une saison où les sommets ont tendance à se présenter sous une seule saveur.

Il est indéniable qu’il existe une différence fondamentale entre la direction d’un individu éblouissant comme Kawakami et la main ferme de Shinohara. Le réalisateur de la sérieRéalisateur de la série : (監督, kantoku) : la personne en charge de l’ensemble de la production, à la fois en tant que décideur créatif et superviseur final. Ils surpassent le reste du personnel et ont finalement le dernier mot. Il existe cependant des séries avec différents niveaux de réalisateurs: réalisateur en chef, assistant réalisateur, réalisateur d’épisodes de série, toutes sortes de rôles non standards. La hiérarchie dans ces instances est un scénario au cas par cas. lui-même y a fait allusion, comme le montre l’une des nombreuses interviews réalisées pour le long métrage Kisekoi S2 sur Newtype en septembre 2025. Compte tenu de son style réfléchi mais finalement plutôt calme, Shinohara nie humblement avoir le type de gravité de ses pairs les plus charismatiques. Bien qu’il existe une tendance dans cette industrie où le magnétisme est corrélé à la flamboyance, Shinohara se trompe manifestement, comme le montre la façon dont ces stars les plus connues du public chantent son nom chaque fois qu’il apparaît dans l’actualité, montrant leur appréciation pour son métier d’une manière amusante. Cela ne se démarque peut-être pas de la même manière, mais la précision technique de Shinohara est grandement appréciée par ceux qui travaillent à ses côtés. Et s’il était placé dans un environnement plus favorable, avec en plus un peu plus d’expérience à son actif, il pourrait conquérir les téléspectateurs avec autant d’enthousiasme. Sa grandeur est peut-être plus difficile à saisir qu’avec ces réalisateurs vedettes plus manifestes, mais son charme n’en est pas moins.

Et ainsi, pensez à la saison 2 de Kisekoi, le projet qui a permis à Shinohara d’être à la hauteur de ce potentiel.

Si vous avez été surpris par la façon dont cette suite s’améliore dans pratiquement tous les domaines, vous aviez le bon état d’esprit. À l’exception des rares remplacements de personnel qui s’améliorent, le résultat le plus naturel pour les séquelles est d’amorcer une légère tendance à la baisse. Le maintien de son niveau d’origine, voire une légère amélioration, sont à l’ordre du jour, mais tout ce qui est plus prometteur flirte avec l’illusion. Pour faire simple, il est courant que les premiers projets soient synonymes d’un investissement plus important et d’équipes plus performantes ; après tout, l’engagement à long terme d’un personnel qualifié est le plus difficile à obtenir, et par nature, les suites s’accompagnent soit d’une base de fans déjà sécurisée, soit de la certitude que la série n’est pas un succès. Ce n’est pas comme s’il n’existait aucun exemple de deuxièmes saisons qui soient des œuvres plus fortes et plus convaincantes, mais vous ne pouvez certainement pas prendre pour acquis de grandes améliorations dans le département de production.

Qu’est-ce qui a permis à Kisekoi de faire un saut si clair, alors ? Nous avons déjà mentionné quelques raisons qui sont entrées en jeu. Il convient de rappeler qu’il ne s’agit que de la quatrième tentative de Shinohara de réaliser une série, et que les deux premiers cas se sont avérés être Black Fox (où il remplaçait en quelque sorte le très occupé Kazuya Nomura) ainsi que l’enveloppe effondrée de A3 qu’il a partagée avec un autre réalisateur prometteur, Masato Nakazono. Kisekoi ressemble à sa première tentative de diriger un projet sérieux, donc une amélioration considérable au moment de la suite est raisonnable. Surtout quand, comparé à la dépression post-WEP, ce projet arrive à un moment où la chaîne de production d’Umehara et certaines parties de CloverWorks sont… florissantes autant que possible tout en étant manifestement trop occupées, disons. Pas idéal, mais clairement un meilleur environnement pour un réalisateur de série plus mature. Directeur de série : (監督, kantoku) : la personne en charge de l’ensemble de la production, à la fois en tant que décideur créatif et superviseur final. Ils surpassent le reste du personnel et ont finalement le dernier mot. Il existe cependant des séries avec différents niveaux de réalisateurs: réalisateur en chef, assistant réalisateur, réalisateur d’épisodes de série, toutes sortes de rôles non standards. La hiérarchie dans ces cas est un scénario au cas par cas..

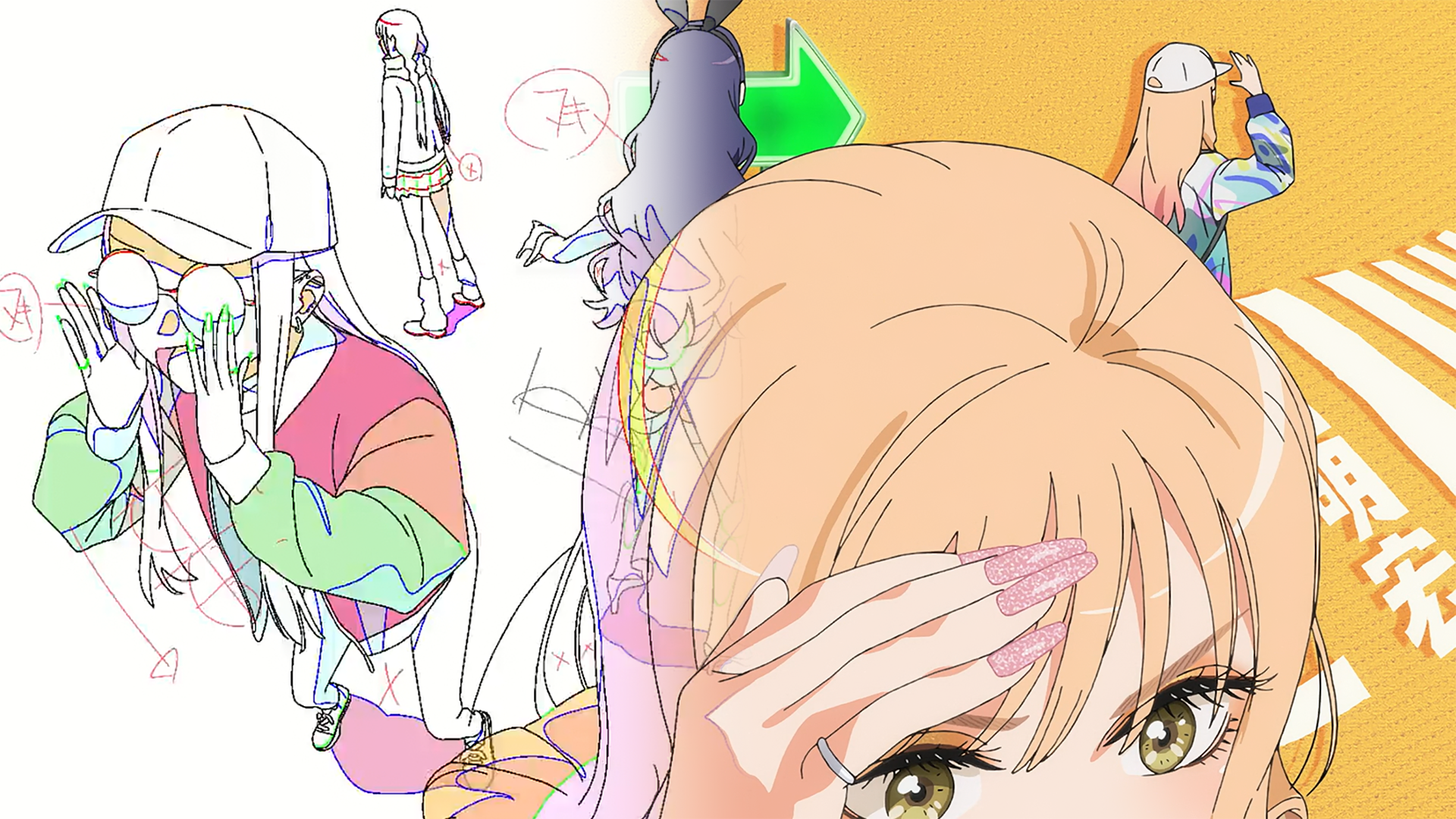

Passer directement au premier épisode de la saison 2, c’est-à-dire Kisekoi #13 suivant la numérotation officielle, met en valeur ces améliorations substantielles à tous les niveaux. Shinohara n’a jamais abandonné ses tendances, mais comme il l’a expliqué dans l’interview Newtype susmentionnée, il souhaitait élargir la gamme d’expression. Selon lui, les trahisons occasionnelles de la réalité objective rendent les choses plus intéressantes tant pour les téléspectateurs que pour les créateurs. Armé de ce nouvel état d’esprit – et de la collaboration d’un certain membre clé de l’équipe de la saison 2 – il s’est lancé dans le storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): les plans de l’animation. Une série de dessins généralement simples servant de script visuel à l’anime, dessinés sur des feuilles spéciales avec des champs pour le numéro de coupe de l’animation, des notes pour la portée et les lignes de dialogue correspondantes. Plus et dirigez cette réintroduction à la série.

Si vous avez l’intention d’évaluer Shinohara, la scène brillante à la fin de l’épisode pourrait être le meilleur exemple de ce dont il est capable cette fois-ci. Entouré d’extravertis lors de la fête d’Halloween à laquelle il a été entraîné, Gojo est obligé de faire face à ses insécurités ; a-t-il vraiment sa place parmi eux, et en fait, a-t-il sa place quelque part lorsque ses intérêts ne sont pas conformes aux normes de genre ? Ces craintes sont exprimées à travers un texte précisément chronométré alors que nous plongeons dans sa psyché, montrant son excellence technique habituelle mais aussi son désir d’augmenter l’abstraction. Shinohara réussit ce nouveau défi d’évoquer quelque chose de plus grand que la réalité matérielle de la scène, et en même temps, joue toujours dans les limites de son décor de manière amusante. Après tout, toute cette scène dure quelques minutes tandis que vous pouvez entendre le chant Nowa préféré de tous (plutôt Haruhily) en arrière-plan. Et ainsi, après être passée des peurs de Gojo à un agréable sentiment d’acceptation, le point culminant de la chanson lui permet immédiatement de pivoter vers une question publique hilarante et inopportune sur la question de savoir si les deux protagonistes sortent ensemble. Que vous soyez Nowa et que vous soyez Shinohara.

80 séquences autour de la scène du karaoké, y compris pratiquement toutes les apparitions de Nowa, ont été dessinées par Hirohiko Sukegawa. Ce n’est pas un hasard: il a fait appel autant que possible à son personnage préféré, étendant ainsi ses fonctions au-delà de la série elle-même. L’équipe lui a permis de dessiner beaucoup de extra illustrations pour accompagner les reprises de chansons rock de Nowa (pourquoi a-t-elle si bon goût ?) tout au long de la saison 2, au point que l’auteur original a repris ses efforts très concentrés. Et ainsi, alors que la saison se terminait, elle a dessiné Nowa en mode oshikatsu… sur le véritable animateur Sukegawa, qui, comme on pouvait s’y attendre, a perdu la tête à ce sujet. De plus, pendant que nous parlons du clip ci-dessus, la façon dont les noms et les âges sont répertoriés rappelle certainement une scène emblématique de FLCL. Je soupçonne qu’un certain assistant réalisateur de la série a inventé ce détail.

Tout comme la fin de l’épisode est excellente, le début l’est aussi. Cette structure est avant tout un grand pas en avant dans l’adaptation. Une grande partie des premières étapes de la deuxième saison repose sur de petits changements dans le flux du matériel source, et je crois qu’ils ont atteint leurs objectifs ; dans le cas du premier épisode, pour nous accueillir à nouveau avec quelque chose qui résume la totalité du charme de Kisekoi, plutôt que de procéder comme si aucune rupture ne s’était produite. Et ainsi, tout comme son prédécesseur le faisait occasionnellement, la saison 2 commence avec une parodie de genre ridiculement amusante dirigée par Kai Ikarashi-une parodie qui sert également à dire au revoir au défunt directeur artistique. (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): La personne en charge du background art de la série. Ils dessinent de nombreux plans de travail qui, une fois approuvés par le réalisateur de la série, servent de référence pour les arrière-plans tout au long de la série. La coordination au sein du département artistique est indispensable: les décorateurs et les concepteurs de couleurs doivent travailler ensemble pour créer un monde cohérent. Ryo Konno.

À mesure que la portée de la série s’élargit, ces aperçus amusants de ses œuvres de fiction dans l’univers s’élargissent également. Ils englobent plus de coins de la carte otaku et deviennent plus étoffés, en particulier dans une adaptation qui les imagine bien plus loin que les aperçus du manga. Suivant la plume d’Ikarashi, celui-ci devient plus… tout. Plus. C’est essentiellement ainsi que Shinohara parle de son ami Ikarashi: quelqu’un en qui vous pouvez avoir confiance non seulement pour obtenir ce à quoi font allusion vos storyboards, mais qui vous surpassera ensuite en l’étendant bien plus loin. TsuCom est une série à la fois dure et loufoque qui est censée vous faire Merde, c’était amusant, et c’est exactement ce que véhicule le travail d’Ikarashi.

Bien que Shinohara ait eu l’idée approximative de cette scène, elle c’est quelqu’un d’autre qui l’a transformé en un véritable storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): Les plans de l’animation. Une série de dessins généralement simples servant de script visuel à l’anime, dessinés sur des feuilles spéciales avec des champs pour le numéro de coupe de l’animation, des notes pour la portée et les lignes de dialogue correspondantes. Plus. Cette même personne lui a donné des idées tout au long de la saison, devenant sans doute le principal responsable du changement de ton de Kisekoi. Il est enfin temps de parler du favori des fans Yuusuke « Nara » Yamamoto, qui a adopté une position proactive dans son rôle nouvellement acquis d’assistant réalisateur de la série. Directeur de la série : (監督, kantoku) : la personne en charge de l’ensemble de la production, à la fois en tant que décideur créatif et superviseur final. Ils surpassent le reste du personnel et ont finalement le dernier mot. Il existe cependant des séries avec différents niveaux de réalisateurs: réalisateur en chef, assistant réalisateur, réalisateur d’épisodes de série, toutes sortes de rôles non standards. La hiérarchie dans ces cas est un scénario au cas par cas. Comme il le note dans l’interview de Newtype qu’il partage avec son bon ami et animateur principal Naoya Takahashi, la portée et les spécificités de ce rôle varient considérablement en fonction de l’environnement et du projet donné. Dans ce cas, la portée de Nara était globale, comme le fait normalement seul le chef de projet ; omniprésent dès les réunions de scénario, et impliqué dans le choix des épisodes où il n’était pas non plus explicitement crédité. Accorder autant d’implication à quiconque devrait avoir un effet, sans parler d’un créateur avec une personnalité aussi audacieuse que celle de Nara.

Dans cette interview, Takahashi souligne les qualités de Nara en tant que réalisateur comme quelque chose d’unique pour son parcours. Je serais largement d’accord avec son point de vue selon lequel, chaque fois que des animateurs de personnages exceptionnels passent à des rôles de réalisateur, ils ont tendance à accorder beaucoup d’importance à la beauté et à la solidité technique des plans, à l’authenticité du jeu des acteurs et au flux mécanique des storyboards. Ce sont bien sûr des qualités positives, et aussi un côté que Nara n’a pas vraiment perdu. Cependant, en changeant de rôle, il est devenu un artiste beaucoup plus investi dans la simple idée de divertir le public et de le surprendre. C’est quelque chose que les fans de Bocchi the Rock ont vraiment apprécié, car ses épisodes de la première saison étaient parmi les moins orthodoxes pour ce qui était déjà une comédie excentrique. Cependant, il convient de noter que le désir de surprendre les téléspectateurs avec une diversité de matériaux est quelque chose que Nara a déjà manifesté (même dans une autre émission de Bocchi !).

En un seul épisode, les raisons qui ont permis à Kisekoi de passer au niveau supérieur tout cela est énoncé assez clairement. Il ne s’agit bien sûr pas d’une cause unique. Nous avons parlé de la croissance de Shinohara, du changement d’approche et de la façon dont l’arrivée de Nara a encore alimenté les deux. Si l’on prend du recul, il est impossible de dissocier ce dernier point de l’état actuel de Bocchi le Rocher ; un vide imprévu qui a fait que non seulement son personnel, mais aussi l’énergie qu’ils transportaient, se sont répandus dans Kisekoi.

Bien qu’il y ait toujours eu un chevauchement entre ces projets en tant que deux séries gérées par le gang d’Umehara, la façon dont son personnel et son côté comique ont pris le contrôle de Kisekoi S2 parle d’elle-même… tout comme le fait que le concepteur de Bocchi, Kerorira, est passé d’animateur occasionnel à celui d’équipe. Soutien. Selon Umehara, ce crédit est censé refléter sa position actuelle en tant que personne qui transcende les projets au sein du studio. En bref, c’est une figure fiable avec les capacités de prise de décision et de communication nécessaires pour aider à tout moment, en plus de sa capacité à dessiner beaucoup.

En ce qui concerne Kisekoi S2, cette charge de travail plus tangible équivalait à une ouverture animée en solo, à une assistance aux effets pour leurs jeux dans l’univers, à un nettoyage des épisodes les plus lourds et à de gros morceaux d’animation clé. Key Animation (原画, genga) : ces artistes dessinent le moments cruciaux dans l’animation, définissant essentiellement le mouvement sans réellement terminer le montage. L’industrie de l’anime est connue pour donner à ces artistes individuels une grande marge de manœuvre pour exprimer leur propre style. pour clôturer la saison. Pour ce premier épisode, ce qui ressort le plus, c’est la séquence où une Marin plutôt brouillonne traverse des montagnes russes émotionnelles en laissant un peu trop libre son imagination ; presque comme si Kerorira avait animé sans cesse une créature rose qui en faisait l’expérience régulièrement. Bravo également au dernier montage, tout le monde remarquant le comportement excentrique de Marin alors qu’une vague d’animation d’arrière-plan organique frappe les fenêtres. Une précision digne de Shinohara entre des mains d’animation compétentes !

Même si des artistes comme lui se démarquent, il est important d’établir que la grande augmentation des valeurs de production est globale, s’étendant au-delà de tout individu. Encore une fois, c’est quelque chose d’étroitement lié au contexte de production de la saison 2 par rapport à son prédécesseur. Bien que nous ne puissions pas sous-estimer le fait que CloverWorks est dans un état de surproduction, d’autant plus que le studio essaie de considérer cela comme positif compte tenu des résultats obtenus, il est également indéniable qu’il y a des améliorations tangibles dans leur infrastructure. La formation de leur personnel (et leur braconnage parfois agressif) a permis de constituer une équipe plus étudiante et mieux préparée. En s’appuyant sur ce terrain solide plutôt que dans le cratère laissé par WEP, le support était tout simplement d’autant plus fort.

Bien qu’il s’agisse d’un solo animé par Kerorira, l’ouverture a été réalisée et scénarisée par Yuki Yonemori. Sa charmante intégration des génériques de production attire le regard, même si je pense que le cœur de la séquence est l’accent qu’il a mis sur les matériaux physiques – quelque chose de la plus haute importance dans une série sur le cosplay. Il convient de souligner que la séquence emprunte de nombreuses compositions à NO LULLABY, un clip vidéo que, j’en suis sûr, quelqu’un d’aussi attiré par l’animation mondiale que Yonemori avait vu à plusieurs reprises. Je crois que la façon dont ils sont traités est transformatrice et apparaît comme un signe de tête respectueux, même si cela aurait mieux plu aux gens s’ils avaient crié à l’équipe d’origine. Compte tenu des règles tacites concernant les mentions explicites d’autres œuvres, l’idée a peut-être été malheureusement rejetée.

Ne vous méprenez pas : Kisekoi S2 connaît un succès unique. Même si je crois que la créativité amusante de Bocchi le propulse tout en haut des œuvres d’Umehara, il y a un argument à faire valoir sur la précision minutieuse – qui n’est pas en contradiction avec une exécution tout aussi vivante – dans la plupart des Kisekoi S2, ce qui en fait la plus grande production de cette équipe. Shinohara lui-même considère que les normes pour des épisodes comme la première de la saison 2 sont excessives pour la télévision. Il ne parlait pas seulement des aspects les plus visibles comme les détails et la finition des personnages, ou même le degré d’articulation de l’animation, mais aussi de la somptuosité de l’entre-deux et de la peinture. Le long temps passé sur les épisodes précédents aide certainement, même si le réalisateur souligne également que le niveau élevé de compétences techniques a considérablement réduit le besoin de reprises, rendant ainsi ce degré d’ambition réalisable. Peut-être que la meilleure façon de décrire leur succès est de dire qu’il s’agit d’une saison très finement réglée ; Une partie de ce secret étant, comme il l’a révélé, une équipe si bonne qu’elle a réussi beaucoup de choses du premier coup.

Cette finesse se retrouve dans le deuxième épisode de la saison, qui par ailleurs produit un changement de ton notable. L’un des principaux points que vous devez comprendre pour apprécier le changement notable de saveur entre les saisons de Kisekoi est que Nara était véritablement partout, aux côtés d’un réalisateur de série. Directeur de la série : (監督, kantoku) : La personne en charge de l’ensemble de la production, à la fois en tant que décideur créatif et superviseur final. Ils surpassent le reste du personnel et ont finalement le dernier mot. Il existe cependant des séries avec différents niveaux de réalisateurs: réalisateur en chef, assistant réalisateur, réalisateur d’épisodes de série, toutes sortes de rôles non standards. La hiérarchie dans ces instances est un scénario au cas par cas. qui était heureux d’absorber ses idées. Et pourtant, tout comme la concentration d’oxygène dans l’atmosphère peut fluctuer, la densité des particules directrice scandaleuses peut fluctuer également (véritable concept scientifique). Ceux-ci ont tendance à être à leur apogée, bien sûr, dans les épisodes que Nara a personnellement réalisés et scénarisés, c’est-à-dire les n°14, n°19 et n°23.

Après le choix de la première de réorganiser les événements afin que les téléspectateurs soient accueillis avec une dose plus complète de Kisekoiness, cette suite nous ramène à une aventure que nous avions sautée. Les réajustements nécessitent de rassembler deux histoires distinctes, mais la prestation de Nara est si confiante que vous n’avez pas l’impression qu’il n’y avait pas de vision claire derrière cela. Bien sûr, nous passons de la suite du rythme des comédies romantiques sur la question de savoir s’ils sortent ensemble au cosplay et aux intrigues axées sur le genre, mais les deux sont livrés à travers des mélanges de styles tout aussi éclectiques.

Nara est toujours prête à passer de la normalité ancrée de Kisekoi à his reminders that animation is composed of assets he can play around with. There’s that familiar sense of comedy built upon quick stylistic shifts whenever he can find a way to sneak it in; changing levels of stylization, of fluidity in the animation, and then subverting your expectations from an entirely new vector when you think you’ve cracked the pattern. Just like the Bocchi anime that episodes like this are so reminiscent of, it’s the consistent sense of surprise that becomes the glue between heterogeneous parts.

Since we talked about the opening sequence, we ought to introduce the ending as well. The closing sequence by VIVINOS is very reminiscent of their Pink Bitch Club series, taking Marin’s crush and her interest in fashion as an excuse to turn her into a bit of a menhera menace.

If we stop and appreciate the once again excellent animation, we can find plenty of examples of seemingly uncanny combinations of ideas leading to a richer outcome. With a director as quick to embrace cartoony aesthetics, you could assume that’s the route it’ll head in whenever there are comedic needs, but Nara successfully guides the team to get mileage out of less common approaches. Like, for example, ever so slightly dialing up the realism to make a sequence more amusing. As an embarrassed Marin storms away from Gojo, the level of lifelike detail in which the folds of his disguise are depicted—a bit exaggerated but not so much that they become a caricature—makes him look much creepier and thus funnier in this context. Even when the application of a style is more orthodox, the ability to alternate between them will keep you constantly engaged. After all, the same visit to a sick Marin can have outstanding examples of precision in animation and inherently funny betrayals of space. In a season with many outrageous visual tricks, even the seemingly more standard sequences can be inherently fun to look at.

One detail we’ve neglected to mention is that all those scenes arrived by the hand of the aforementioned main animator, Naoya Takahashi. Speaking to Newtype, he simplified the evolution of his role as going from a tactically deployed weapon across important moments in the first season, to handling large chunks at a time for the sequel. This is not to say that he no longer handled climactic moments, since we’re talking about an animator with a hand in the very last scene of the season. However, it’s true that he halved his appearances so take he could take over many cuts whenever he showed up as either key animator or supervisor.

Applied to episode #14, that meant drawing key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. for virtually every single shot in the first half; the only small exceptions being Odashi and the regular Yohei Yaegashi making cute guest appearances, in rather different ways. Nara is particularly effusive about Takahashi’s mindset, as an animator whose interests are tickled by seemingly troublesome cuts that he’ll complicate even further, but it’s worth noting that the entire second half received the same holistic treatment by Maring Song. Given that its animation demands are just as diverse, the challenge couldn’t have been any easier.

Even with those assistants and the help of a solid lineup of 2nd key animators, having the episode’s two animation directors penning every single cut in the first place is quite the ask. And keep it in mind: it was an ask, not a spur-of-the-moment happening but a foundational idea in planning Kisekoi S2. Those Newtype features confirm as much, saying it was an episode conceived to be animated by a small team. While this one is noteworthy in how far they went with it, the desire to keep animation teams small is a defining trait of Umehara’s production line in recent times. From a creative standpoint, there’s an obvious reason to chase that goal: the natural sense of cohesion and full realization of a better-defined vision that you can get out of small teams. And from a management level, the idea that you may be able to offload this large a workload to just a few people—at least for certain tasks—is a dream come true.

While it’s positive that viewers have started paying attention to the composition of teams (who is part of them, their size, roles, etc), many are a bit too quick to assume that seeing fewer animators credited is immediately a sign of a healthier, straight-up superior production. Instead, they should be asking themselves if such a team was a natural fit for the production circumstances, and whether the level of ambition and quality standards match their possibilities.

Circling back to Kisekoi S2, then, we can say that episodes like this manage to maintain—and occasionally even raise—the project’s already impressive technical floor despite the small team. And what about the larger picture? Did this approach eventually push the production off the rails? Although things got tighter by the end, we can now say that it weathered the storm without requiring the level of unthinkable individual feats that protected the likes of Bocchi. In that regard, it’s worth noting that Kisekoi S2 showed an interesting level of restraint. Small teams of animators, but never as far as this one episode. A mere two episodes with a singular animation director, instead opting for duos as its default. Part of this comes down to the improvement of CloverWorks’ infrastructure (not to be confused with their planning) that we talked about earlier, but it’s also about that evolution in Umehara’s mindset; away from his most aggressive tendencies, less allergic to the concept of compromising, and instead interested in finding ways to minimize the negative effects from that.

It’s another one of Umehara’s favorite weapons that takes over the show with the next episode: character animation ace Tomoki Yoshikawa, who makes his debut as storyboarder and episode director. If his peers viewed Nara as a very entertaining aberration, Yoshikawa embodies straightforward excellence in his breed. As an animator, Yoshikawa’s work feels performed in a way that few artists’ do; so specific in its posing and demeanor that you feel as if the characters were actors who’d just been briefed by the director. And now that he genuinely occupies that position, you get that philosophy applied to an entire episode—often through his own redraws. The way people interact with objects and people’s gestures constantly stand out as deliberate. The way he accomplishes it makes his ostentatious brand of realism not particularly naturalistic, but its technical greatness and sufficient characterfulness justify its braggadocio air. Perhaps this is the horseshoe he shares with Nara: one, a director so imaginative that he gets away with making the artifice painfully obvious, the other, an animator so good at articulating characters that he’s happy with showing you the strings with which he puppeteers them.

Despite yet another charismatic lead artist having a visible impact, Kisekoi S2’s overarching identity is too strong to ever disappear. Instead, what happens is that the two tendencies tend to mix with each other. Yoshikawa’s deliberate acting doesn’t risk coming across as too clinical and serious, as his precise posing occasionally becomes a source of humor as well; for an obvious example, a binoculars-like shot is followed up by the type of silly pose that Marin is likely to adopt when her nerdy side takes over. The switches to blatantly cartoony animation can occur without ditching the calculated staging, and for that matter, without ditching Yoshikawa’s pen either—he personally key animated some of them as well.

The real highlight of the episode, though, is in Amane’s backstory. At this point, it should be obvious that Yoshikawa is more than a cold, technically proficient animation machine. He once again shows that much with a stunning flashback focused on the main duo’s new friend and his encounter with crossplay, which helped him forge an identity he’s finally comfortable with. Through some of the most ethereal drawings in the entire show (many by Yoshikawa himself), we witness his first experiences with makeup, wigs, and dresses. We see neither his face nor reflection, but it quickly becomes obvious that it’s because his past, regular self was one that he’d never been comfortable with. It’s impossible not to feel the contrast with his current persona, highlighted by all the cuts to the present clearly showing a happy face after so much obscuration of his expressions. The Amane of right now, the person cosplaying a female character while hanging out with Marin and Gojo, is the self that he loves and proudly projects outward.

This type of conflict is by no means new to Kisekoi. After all, Gojo’s own insecurities are also rooted in traumatic rejection over his gendered interests; and of course, Marin being a widely beloved, popular girl with some very male-coded hobbies is the flipside to his situation. Up until now, though, none of those situations had been presented in such striking fashion. If we add to that the way that Kisekoi’s exploration of otaku spaces widens—and this is only the beginning—the message of acceptance that had always been attached to the series starts feeling more meaningful.

The following episode ventures further in that regard. Although it’s the first chance for the production to take a bit of a breather, one aspect took a lot of work and it very much shows: the depiction of PrezHost. As is the norm with this season, an in-universe work briefly depicted in the manga becomes a fully fledged production effort within its anime adaptation. The beautiful designs by WEP’s Saki Takahashi and the evocative compositions it dashes out when necessary sell the appeal of the series, though it’s the concept itself that feels most important.

Even though Kisekoi rejects conforming to the preconceptions about what individuals ought to enjoy according to their age or gender, constantly doing so while only ever portraying danseimuke fiction (or types of work otherwise largely tolerated by men) would make its plea for acceptance ring rather hollow. This makes their fancy depiction of a shoujo manga turned popular live-action drama such a great choice, because it feels like it understands what teenage girls and families alike—including some boys, awkward about it they are—would get really into. I have to admit that, given the extremely obvious Ouran vibes of this fake series, I’d have loved to see much more overt mimicry of Takuya Igarashi’s direction; at best, Mamoru Kurosawa’s storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime’s visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. More and its SHAFT flavor merely evoke vibes that feel like a distant stylistic cousin. That said, beautiful animation dedicated to something that strengthens your whole series’ message is hardly a reason to complain.

Between WEP’s early moments of excellence and his work across the 22/7 short films, Wakabayashi earned himself a reputation as a breathtaking director, the type that invites you into ethereal spaces where mundanity feels divine. Mind you, there is still plenty of room for delicacy and elegance across his boards here. Within an arc that strongly emphasizes collective work and the reliance on everyone’s specific skills, episode #17 allows the fundamentally subdued animation to do the talking; Gojo’s expert movements contrast with Marin’s well-meaning flubs, yet she’s the one who irradiates confidence with her body motion when she’s in her field. The intricacies of seemingly mundane animation tell us a lot, just by swinging from one of Marin’s beastly lunches to Gojo’s delicate eating as drawn by Shinnosuke Ota. Even that otherworldly vibe of Wakabayashi’s direction is channeled through the depiction of light, dyeing the profiles of the lead characters when they’re at their coolest and most reflective.

However, those are merely the gifts that you’ll find hidden within the bushes—or rather, in a very exuberant, colorful jungle. Wakabayashi and episode director Yuichiro Komuro, an acquaintance from WEP who already did solid work in Kisekoi S1, meet this sequel on its own terms. Stronger comedic edge, but also the incorporation of different genres we hadn’t explored before? Playful emphasis on the farcicality of animation assets, as well as a much higher diversity of materials? If that is the game we’re playing now, Wakabayashi will happily join everyone else. And by join, I mean perhaps best them all, with a single scene where Marin squeals about her crush being more densely packed than entire episodes; horror buildup, an imaginative TV set, slick paneling that breaks dimensions and media altogether, and here’s a cute shift in drawing style as a final reward. Wakabayashi may be playing under someone else’s rules, but he’s far from meek in the process. Episode #17 is out and proud about being directed, with more proactive camerawork than some hectic action anime and noticeable transitions with a tangible link to the narrative.

For as much as episodes like this rely on the brilliance of a special director, though, this level of success is only possible in the right environment. This is made clear by one of the quirkiest sequences: the puppet show used for an educational corner about hina dolls. The genesis is within Wakabayashi’s storyboards, but the development into such a joyful, involved process relied on countless other people being just as proactive. For starters, the animation producer who asked about whether that sequence would be drawn or performed in real life, then immediately considered the possibility of the latter when Wakabayashi said it could be fun. There’s Umehara himself, who’d been watching a documentary about puppeteer Haruka Yamada and pitched her name. The process this escalated into involved all sorts of specialists from that field, plus some renowned anime figures; no one better than Bocchi’s director Keiichiro Saito to nail the designs, as dolls are an interest of his and he has lots of experience turning anime characters into amusing real props. Even if you secure a unique talent like Wakabayashi, you can’t take for granted the willingness to go this far, the knowledge about various fields, and of course the time and resources required for these side quests.

And yet, it’s that emphasis on clinical forms of animation that also makes it feel somewhat dispassionate—especially after the playfulness of Wakabayashi’s episode. The delivery is so fancy that it easily passes any coolness test, and it certainly has nuggets of characters as well; watching the shift in Marin’s demeanor when she’s performing makes for a very literal, great example of character acting in animation. But rather than leaning into the fun spirit of a school festival, the direction feels very quiet and subservient to an artist who can lean towards the mechanical. It’s worth noting that the most evocative shots in the entire episode, which break free from its cold restraint, come by the hand of Yusuke Kawakami. Those blues are a reminder of the way he already stole the show once, with that delightful eighth episode of the first season.

Kisekoi S2 is certainly not the type of show to dwell in impassionate technicality for too long, so it immediately takes a swing with another fun episode captained by Nara. A leadership that this time around doesn’t merely involve storyboarding and direction, but even writing the script as well. Given that the animation director is Keito Oda, it ends up becoming quite the preview for the second season of Bocchi that they’re meant to lead together. His touch can be felt through the spacious layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. and the character art itself, with scenes like the one at the karaoke feeling particularly familiar. A noticeably softer feel within a series where the designs normally lean in sharper directions.

Even though Nara mostly plays with regular tools for this episode, the same eclecticism we’ve been praising so far is all over the episode. At no point can you be sure about which technique, palette, and type of stylization he’s going to deploy when depicting Marin’s struggles. This helps spice up an episode that is otherwise a simple breather. Weight gain scenarios in anime rarely lead to a fun time; you don’t have to start considering whether they’re problematic or not to realize that they’re formulaic and repetitive. However, within a show where bodies are meaningfully explored and thanks to Nara’s amusing resourcefulness, it becomes yet another entertaining episode.

Additionally, there is a reason why we said that the director mostly uses regular tools in episode #19. The highlight is a sequence built upon a 3D scan of a real park, in a process that took 9 months to complete. Although there are technical points of friction like Marin’s lack of a projected shadow, this was a tremendous amount of effort applied to a fundamentally compelling idea. Within regular comics, a sudden switch to a series of identical panel shapes feels unnatural. In the context of a series about cosplay, that’s enough to tell that someone is taking photos. But what about anime (and more broadly, film) where the aspect ratio is consistent? A solution can be to reimagine the whole sequence as a combination of behind-the-camera POV and snapshots that don’t reject the continuity.

While on the surface it might seem like a more modest showing, episode #20 is—in conjunction with the next one—a defining moment of Kisekoi S2. Director and storyboarder Yuuki Gotou is still a bit of a rookie in this field, but may prove to be one of the best scouting moves for the team. Alongside the small changes in the script, the direction toys with the themes of the series in a way that casually solidifies the entire cast. Gojo and Marin attend a cosplay event and come across acquaintances, including multiple friend-of-a-friend scenarios. Those involve someone who, in the manga, is merely mentioned as having been too busy to attend. In the end, we don’t know much about her, and she doesn’t even register as a person. What does Gotou’s episode do, though? It transforms the manga’s plain infodumping about cosplay culture into a fake program that stars her as the host, which makes the eventual reveal that she couldn’t show up more amusing and meaningful; now she actually is a person, albeit a pitiful one. The delivery of the episode is enhanced by similar small choices, in a way that is best appreciated if you check it out alongside the source material.

The immediate continuity in the events links that episode to #21, which also underlines the essence of season 2’s success. I’m sure we’ve all witnessed discourse about anime’s self-indulgent focus on otaku culture at some point. The very idea of acknowledging its own quirks and customs is framed as an ontological evil, though really, those complaints amount to little more than cheap shots at easy targets that people can frame as progressive, refined stances. Were they truly that thoughtful about cartoons, people would realize that such anime’s common failing isn’t the awareness and interest in its surrounding culture—it’s the exact opposite. Anime isn’t obsessed with otaku, but rather with going through familiar motions and myopically misrepresenting a culture that is much broader than we often see. Every late-night show that winks at a male audience about tropes they’ll recognize is blissfully unaware of the history of entire genres and demographics; and for that matter, about the ones that it’s supposed to know as well, given how many gamified Narou fantasies fundamentally don’t understand videogames.

Due to Marin’s choices of cosplay and the unbalanced presentation of the first season, Kisekoi risked leaning a bit in that direction as well. But with a series that genuinely wants to engage with the culture it explores, and a team willing to push its ideas even further, that simply couldn’t come to pass. The most amusing example of this across two episodes is Marin’s cosplay friends, as women who feel representative of distinct attitudes seen in female otaku spaces. From the resonant ways in which proactive fandom is linked to creative acts to the jokes they make, there’s something palpably authentic about it. Nerdy women don’t morph into vague fujoshi jokes, but instead showcase highly specific behaviors like seeing eroticism in sports manga that read completely safe to people whose brains aren’t wired the same way. Kisekoi S2 gets a lot of humor out of their exaggerated antics—both #20 and #21 are a riot about this—but these are just one step removed from real nerds you wouldn’t find in many anime that claim to have otaku cred.

This exploration continues with the type of fictional works that motivate their next cosplay projects. Just like PrezHost felt like a spot-on choice for a group of regular teenagers, an indie horror game like Corpse is perfect for this nerdier demographic of young adults and students; if you wanted to maximize the authenticity, it should have been a clone of Identity V as that was a phenomenon among young women, but their slight departure still becomes a believable passion for this group. And most importantly, it looks stunning. Following the trend you’ve heard about over and over, a loosely depicted in-universe game becomes a fully-fledged production effort led by specialists—in this case, pixel artist narume. It’s quite a shame that, no matter how many times I try to access the website they made for the game, it doesn’t become something I can actually play.

The purposeful direction of Haruka Tsuzuki in episode #21 makes it a compelling experience, even beyond its thematic success. Though in a way, its most brilliant scene is still tied to that—Marin’s subjectivity being so clearly depicted is one of the ways in which Kisekoi pushes back against common failings of the genre, after all. When she misunderstands what Gojo is buying, diegetic green lights flash green, like a traffic light signaling his resolve to go ahead. Marin’s panic over the idea of getting physically intimate coincides not just with a camera switch to show an adults-only zone of the store nearby, but also with the lights turning red. She doesn’t exactly feel ready… but the more she thinks about it, the lights switch to pink. If I have to explain what this one means, please go ask your parents instead.

Season 2 thrives because of this broader, deeper depiction of cosplay as an extension of otaku culture. As we mentioned earlier, it makes the message of acceptance feel like it carries much more weight; with a palpable interest in more diverse groups of people, the words of encouragement about finding your passions regardless of what society expects you to do have a stronger impact. Since the preceding season faltered by focusing on arcs where these ideas were still raw, while also introducing biased framing of its own, there’s a temptation to claim that Kisekoi S2 is superior because it stuck to the source material even more. And let’s make it clear: no, it did not. At least, not in those absolute terms.

There is an argument to be made that it better captures the fully-developed philosophy of the source material; the argument is, in fact, this entire write-up. That said, much of our focus has also been on how Shinohara’s desire to increase the expressivity and the arrival of Nara have shifted the whole show toward comedy. Kisekoi has always had a sense of humor, but there’s no denying that this season dials up that aspect way beyond the source material. That has been, as a whole, part of the recipe behind such an excellent season.

And yet, we should also consider the (admittedly rare) occasions where it introduces some friction. If we look back at episode #20, one of the highlights in Gotou’s direction is the goofy first meeting between Akira and Marin. Since we’re taking a retrospective look after the end of the broadcast, there’s no need to hide the truth: Akira has a tremendous crush on her. However, their entire arc is built upon everyone’s assumption that she hates Marin, as she gets tense and quiet whenever they’re together. The manga achieves this through vaguely ominous depictions of Akira, which would normally be read as animosity but still leaves room for the final punchline. The adaptation mostly attempts to do the same… except their first meeting is so comedic, so obvious in the falling-in-love angle, that it’s impossible to buy into the misdirection. Every now and then, it’s in fact possible to be too funny for your own good.

If we’re talking about the relative weaknesses of the season, episode #22 is a good reminder that outrunning the scheduling demons—especially if you enjoy taking up creative strolls to the side—is hard even for blessed projects. Conceptually, it’s as solid as ever. Marin’s sense of personhood remains central to everything, with her own struggles with love and sexuality being as carefully developed (if not more) than anything pertaining to Gojo. Being treated to another showcase of Corpse’s beautiful style is worth the price of admission, and you can once again tell that Fukuda understands nerds as she writes them salivating over newcomers’ opinions on their faves. It is, though, a somewhat rougher animation effort despite all the superstars in various positions of support. While the decline in quality is only relative to the high standards of Kisekoi S2, seeing what caliber of artist it took to accomplish an acceptable result speaks volumes about how tight things got.

Thanks to the small structural changes to the adaptation, this episode is able to reinforce the parallels between Akira’s situation and the world’s most beloved cosplayer Juju-sama (sentence collectively written by Marin and her sister). Sure, Juju’s got a supportive family and has been able to chase her dreams since an earlier age, but there have always been hints that she holds back somewhat. As a cosplayer with utmost respect for the characters, she never dared to attempt outfits where her body type didn’t directly match that of the original. This is why we see similar framing as that of a student Akira, feeling cornered before she stumbled upon a space to be herself. Nara may be an outrageous director, as proven by how quickly he unleashes paper cutout puppets again, but you can see his a subtler type of cheekiness in his storyboards as well; cutting to Juju’s shoes with massive platforms during a conversation about overcoming body types is the type of choice that will make you smile if you notice it.

On top of that thematic tightness and meaningful direction, episode #23 is also an amazing showcase of animation prowess. Separating these aspects doesn’t feel right in the first place; the compelling ideas rely on the author’s knowledge about the specifics of cosplay, which are then delivered through extremely thorough and careful animation. The likes of Odashi and Yuka Yoshikawa shine the best in that regard, though it’s worth noting that the entire episode is brimming with high-quality animation—and most importantly, with respect for the process of creating things as an expression of identity. Be it the Kobayashi-like acting as Juju storms out during a pivotal conversation about that, or a familiar representation of cosplay as a means to reach seemingly impossible goals by Hirotaka Kato, you can never dissociate the episode’s beautiful art from its belief that making things can allow us to be our real selves.

Again, it’s no secret that an episode like #23 was produced under strict time constraints; perhaps not in absolute terms, but very much so when you consider its level of ambition. In the context of not just this series but the production line we’ve been talking about all along, what’s interesting isn’t the achievement itself, but how it relates to an evolution we’ve observed before. Umehara’s more considered stance and CloverWorks’ improving infrastructure have been recurring themes, but there’s been one key piece of information relating to both that we’ve been keeping a secret. For as much as we’ve referred to this team as Umehara’s gang, which it very much is, you may have noticed that earlier we talked about a separate animation producer—the position that Umehara held in previous projects. So, what happened here?

As he has alluded to on Twitter but more extensively talked about in his Newtype interview, Umehara is not just aware of CloverWorks’ changes, but also quite hopeful about its up-and-coming management personnel. In his view, most of them are just one piece of advice away from figuring out the tricks to create excellent work. And yet, being the animation producer, he tends to be too far from the trenches for those less experienced members to come to him for advice… unless things have gotten really dire. That is, to some degree, simply not true; Umehara is too emotionally invested in the creative process to separate himself from it, no matter what his position at the company is. However, it’s correct that production assistants are more likely to go to their immediate superior rather than someone two steps above when they’ve simply got some doubts. And thus, Umehara has been the production desk for Kisekoi S2, whereas Shou Someno has replaced him in the producer chair.

The first-hand advice Umehara has been able to give will surely be meaningful for the careers of multiple production assistants. And just as importantly, Kisekoi S2 has been an excellent lesson for him. Right after the broadcast of episode #23, and even acknowledging the lack of time, Umehara expressed his delight about what the team had accomplished for the one episode where he was not at all involved in the management process. That future he dreamed of, where the quality of his production line’s output could be maintained without his constant presence, has finally come. Chances are that it could have come faster and less painfully if he hadn’t been so afraid of delegation before, if this team’s well-meaning passion had been channeled in more reasonable ways. Whatever the case, this feels like a positive change if we intend to balance excellent quality with healthier environments… as much as you can within the regime of a studio like this, anyway.

Our final stop is an all-hands-on-deck finale, with Shinohara being assisted by multiple regulars on the team. Though they all made it to the goal with no energy to spare, the sheer concentration of exceptional artists elevates the finale to a level where most people would never notice the exhaustion. The character art retains the polish that the first season could only sniff at its best, and the animation is thoroughly entertaining once again; a special shout-out must go to Yusei Koumoto, who made the scene that precedes the reveal about Akira’s real feelings for Marin even funnier than the punchline itself.

More than anything else, though, the finale shines by reaping the rewards of all the great creative choices that the season has made beforehand. In contrast to the manga, where Corpse was drawn normally, having developed a distinct pixel art style for it opens up new doors for the adaptation. The classic practice of recreating iconic visuals and scenes during cosplay photoshoots is much more interesting when we’re directly contrasting two styles, each with its own quirks. The interest in the subject matter feels fully represented in an anime that has gone this far in depicting it, and in the process, likely gotten more viewers interested in cosplay and photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process.. Perhaps, as Kisekoi believes, that might help them establish an identity they’re more comfortable with as well.

Even as someone who enjoyed the series, especially in manga form, the excellence of Kisekoi S2 has been truly shocking. I wouldn’t hesitate to call it the best, most compelling embodiment of the series’ ideas, as the lengths they went to expand on the in-universe works have fueled everything that was already excellent about Kisekoi. It helps, of course, that its series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. has grown alongside the production line, especially with the help of amusing Bocchi refugees. Despite a fair amount of change behind the scenes and the exploration of more complex topics, the team hasn’t forgotten they’re making a romcom—and so, that stronger animation muscle and more refined direction also focus on making the characters cuter than ever. Given that we’re sure to get a sequel that wraps up the series altogether, I can only hope we’re blessed with an adaptation this inspired again. It might not dethrone Kisekoi S2, but if it’s half as good, it’ll already be a remarkable anime.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites’brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites’brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()